Music Theory is a topic with near-endless concepts and techniques… But luckily, for modern producers, it’s all about MIDI and computer composition, not conducting an orchestra or learning to play a live instrument.

By the end of this series (or even this article), you will have a solid understanding of Theory and how to apply it to production in order to quicken and enhance workflow.

After a while, it will be so second nature that you won’t even realize you’re using it!

THIS ARTICLE WILL INCLUDE THE BASIC CONCEPTS OF MUSIC THEORY:

- Scales, keys, and the notes they are composed of

- Chords

- Harmonies and Melodies

- How to implement these concepts to enhance your workflow, skills, and knowledge

Table of Contents

- BREAKING IT DOWN

- 432Hz vs 440Hz

- KNOWING THE PIANO ROLL

- TO CREATE A MAJOR SCALE:

- TO CREATE A NATURAL MINOR SCALE:

- PRO TIP: KEEPING IT REAL

- SHARPS AND FLATS

- MAJOR CHORDS

- MINOR CHORDS

- PRODUCER THEORY: CHORD CODES

- ROMAN NUMERALS

- SAVE YOUR MAPS

- 7TH, 9TH, 11TH, 13TH CHORDS

- DEFINITIONS TO BE FAMILIAR WITH:

- SCALE MODES

- FINAL THOUGHTS

BREAKING IT DOWN

In order to comprehend Theory as it applies to music production, you must first understand that pitch, scales, and even Music Theory itself is just a system of relative tones and frequency-values (notes).

Similar to language, these pitches evolved over time into what you recognize today.

If you live in North America, the scale systems you use are defined as ‘Western Music.’ In other regions, this varies. Western Music is your native language, so to speak, with a total of just 12 frequency values (notes) to base your scales on.

When listening to something like a melody, for example, it’s not about the actual note, but rather the sequence of notes and the relationship (distance) between them that defines the tune.

Think about it… do you really know what note Happy Birthday starts on? No, right?

This is because it can be different every single time you hear it but always sounds the same regardless of the initial note. As long as the distance between the notes is the same, of course.

There are many confusing aspects to Music Theory, but once they’ve been broken down, it will click faster than your metronome.

432Hz vs 440Hz

Before we get started, I felt the need to quickly mention this all-too-famous debate/tuning standard for a second.

Since the way we hear music is based on the relationships between frequencies, not the frequency values themselves, there are various tuning systems to help you figure out which frequency an instrument is outputting.

This is represented in the digital realm as Sample Rates, which is an extremely extensive topic for a future article.

To keep it simple, there are 2 that remain relevant in Western Music today. I’m sure you’re familiar with the 440Hz vs 432Hz debate, or ‘conspiracy theory’ if you will.

Here is the main takeaway without getting too deep into it, if you’re not familiar:

- 440Hz 一 the standard accepted pitch reference for tuning musical instruments in America (also known as concert pitch)x.

- 432Hz 一 an alternative pitch, argued by some to be superior due to spiritual beliefs or personal preference.

Most music you hear and create today is written in 440Hz Tuning, but just note that if you’re working on an existing song, sample, or instrument and nothing seems to be in key, it’s most likely because it was written in 432Hz Tuning.

Neither is to be considered better than the other and truthfully it’s nearly impossible to tell the difference. Although the frequencies are slightly different, the 12 notes and their respective relationships remain the same.

Forget about it for now, and always work in 440Hz until you’ve mastered this concept and Theory in general.

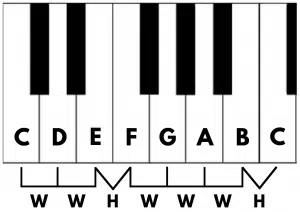

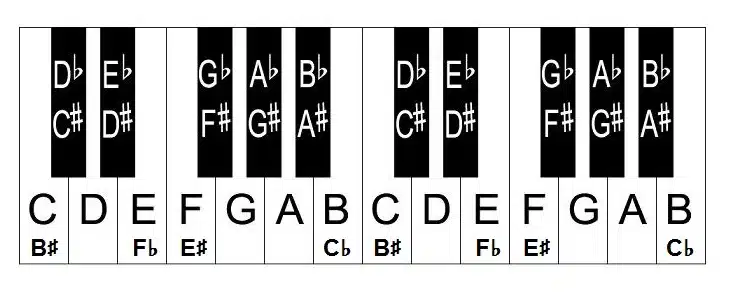

KNOWING THE PIANO ROLL

The easiest way to understand these concepts is with the help of your visual aid and compositional partner: the Piano Roll.

Visually, you can see that each octave of the piano contains 7 white keys and 5 black keys (12 in total):

- The white keys 一 offer notes within the ‘natural’ scale (C, D, E, F, G, A & B).

- The black keys 一 identify Sharps and Flats (described below).

They allow you to work within scales other than those of a ‘natural’ variant.

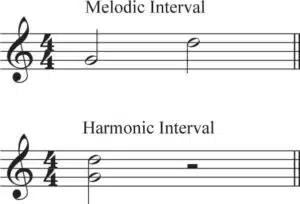

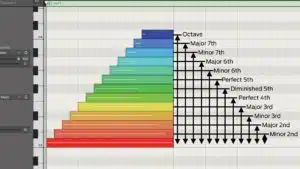

INTERVALS: The space (distance) between 2 notes. They are the key to building harmonic relationships.

- When played in sequence 一 it’s considered a Melodic Interval (like a monophonic melody).

- When played simultaneously 一 it’s considered a Harmonic Interval (a chord).

A HALF STEP (SEMITONE): The distance between any two adjacent keys, white or black. It is the smallest interval. Starting from a white key and going to the black key right next to it is considered a half step (C to C#).

A WHOLE STEP: An interval of 2 semitones (two half steps). The interval between C and D (starting at C) is considered a whole step because the distance was two half-steps away.

Western Musical Scales are built off of predetermined intervals of both whole and half steps. Traditionally, each scale is composed of 7 (of the 12) notes you have access to.

If you know the formula of any given type of scale, you can construct it just by counting. No knowledge or memory of all the notes within a particular scale is needed.

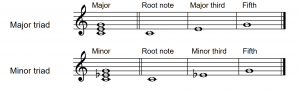

CHORDS: Defined based on a series of whole and half steps, along with more advanced intervals, such as 3rds, 4ths, Major 5ths, 7ths, and so on. They are a combination of three or more notes. The most common 3-note chord is called a Triad.

The intervals between notes of a Major and Minor chord are always the same, the difference being just 1 semitone (half step). So, if you know 1 Major and/or Minor chord, you know them all!

Apart from the basic Major/Minor Triad, there are many variations created by a wide variety of transpositional functions, such as flattening the last note; giving you a Diminished 5th.

TO CREATE A MAJOR SCALE:

Start at any note (called the root note), and count up the scale using this interval pattern:

- Whole Step (W)

- Whole Step (W)

- Half Step (H)

- Whole Step (W)

- Whole Step (W)

- Whole Step (W)

- Half Step (H)

» Major Scales 一 produce a lighter, happier vibe with more emphasis on major chords than minor (although there should be a healthy balance of both).

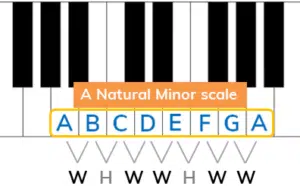

TO CREATE A NATURAL MINOR SCALE:

Start at any note, and count up the scale using this interval pattern:

- Whole Step (W)

- Half Step (H)

- Whole Step (W)

- Whole Step (W)

- Half Step (H)

- Whole Step (W)

- Whole Step (W)

» Minor Scales 一 produce the opposite effect; a sadder, melancholy feeling. However, they can also be used in a more uplifting sense as well. They put an emphasis on minor chords over major.

PRO TIP: KEEPING IT REAL

It’s only half true that Major and Minor chords automatically convey happy and sad vibes. In reality, it’s about how you construct and implement them, along with the sequence in which they play.

Hence, most modern EDM, Hip-Hop, Pop, and Rock songs are written (believe it or not) on a Minor Scale, going against more ‘conventional’ beliefs.

- The key to making a song possess that ‘happy’ feel is by ensuring the notes and chords are in an upwards sequence.

- To convey a ‘sadder’ feel, it entails the opposite: the notes and chords are in a downwards sequence.

Keep in mind that there should always be a healthy balance of both, and you should always return back to your initial starting point (back to the root, in other words).

When looking at your piano roll, the process of returning to your initial position is known as ‘the roller coaster effect,’ as I’m sure you can see why.

SHARPS AND FLATS

Sharps and flats fall into a musical category called accidentals. They represent alterations to ‘natural’ notes, such as C, D, or B.

One of the most puzzling concepts to wrap your head around, especially when first starting out, is the many musical double meanings, such as Sharps (♯) and Flats (♭).

- Sharp means to go up (to the right) by a half step/semitone.

When going from a white key up to a black key, you will consider that note a Sharp (♯). For instance, if you started out at G and went up a half step — that would be considered G♯. This is because G♯ is one half-step higher than the natural note.

- Flat means to go down (to the left) by a half step/semitone.

When going from a white key down to a black key (below it), you will consider that note a Flat (♭). For instance, if you started out at G and went down a half step — that would be considered G♭. This is because G♭ is one half-step lower than the natural note.

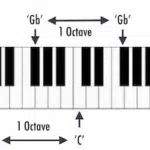

Let’s take a look at the piano to visualize this easier:

» When defining sharps and flats, any pitch can be given more than one note name. Yes, including the white keys. For example, G sharp and A flat are played using the same key on the keyboard. They sound the exact same.

You can also write the F natural as ‘E sharp,’ as F natural is the note that is a half step higher than E natural, which is the definition of E sharp.

Notes that have different names but sound the same are called Enharmonic notes.

Sharp and flat signs can be used in two ways:

- They can be included as part of a key signature

- They can mark accidentals

If most of the C’s are going to be sharp, then a sharp sign will be put in the ‘C’ space at the beginning of the staff, in the key signature.

If only a few of the C’s are going to be sharp, those C’s are marked individually, with a sharp sign right in front of them.

A note can also be double sharp or double flat:

- A double sharp is 2 half steps (1 whole step) higher than the natural note

- A double flat is 2 half steps (1 whole step) lower than the natural note.

NOTE: Triple, quadruple, etc. sharps and flats are pretty rare, but follow the same pattern; every sharp/flat raises/lowers the pitch by one more half step.

MAJOR CHORDS

When talking about Major and Minor chords, we will be using them in their most basic (Triad/3-note) form, for now.

» The formula for any given Major Chord is 0-4-7.

» For this example, it will be: C-E-G (C Major):

You can look at a Major Chord Code as:

- The Root Note (0)

- Major 3rd (4)

- And Perfect Fifth (7) combined.

Your root note, for this example, is C (0). Your Major 3rd would be E because it is (4) semitones away from the root note. Your Perfect 5th would be G because it is (7) semitones away from the root note.

The same formula applies for all Major chords, regardless of the root note you begin with. For example, a Perfect Fifth will always be 7 semitones from the root note.

THE 12 MAJOR CHORDS AND THE NOTES WHICH FORM THEM:

- C Major 一 C E G

- C Sharp Major 一 C♯ E♯ G♯

- D Major 一 D F♯ A

- E Major 一 E G♯ B

- E Flat Major 一 E♭ G B♭

- F Major 一 F A C

- F Sharp Major 一 F♯ A♯ C♯

- G Major 一 G B D

- A Major 一 A C♯ E

- A Flat Major 一 A♭ C E♭

- B Major 一 B D♯ F♯

- B Flat Major 一 B♭ D F

MINOR CHORDS

» The formula for any given Minor Chord is 0-3-7.

» For this example, it will be: C-E♭-G (C Minor).

You can look at a Minor Chord Code as:

- A Root note (0)

- Minor Third (3)

- Perfect Fifth (7)

Your root note, for this example, is C (0). Your Minor 3rd would be E♭because it is (3) semitones away from the root note. Your Perfect 5th would be G because it is (7) semitones away from the root note.

THE 12 MINOR CHORDS AND THE NOTES WHICH FORM THEM:

- C Minor 一 C E♭ G

- C Sharp Minor 一 C♯ E G♯

- D Minor 一 D F A

- E Minor 一 E G B

- E Flat Minor 一 E♭ G♭ B♭

- F Minor 一 F A♭ C

- F Sharp Minor 一 F♯ A C♯

- G Minor 一 G B♭ D

- A Minor 一 A C E

- A Flat Minor 一 A♭ C♭ (B) E♭

- B Minor 一 B D F♯

- B Flat Minor 一 B♭ D♭ F

» Minor chords are the same as Major Chords, except for one vital difference: Instead of the 2nd note being 4 semitones (2 whole steps) from the root note, a Minor Chord is 3 semitones (1 ½ steps) from the root note.

KEEP IN MIND: Not every chord pattern will work within your particular scale if it does not contain the chord’s root note and type.

PRODUCER THEORY: CHORD CODES

If you’re confused at all, you can start off learning by memorization. This is known as Chord Coding. For each code, start at 0 (for the root note), and count upwards to the next note in the code.

» Memorization and counting are key here.

These codes are universal and do not change, regardless of the type of Major or Minor Triad being played. For instance, the Major Chord Code is: 0-4-7 as we just discussed, and the Minor Chord Code is: 0-3-7.

CHORD-PLAYING HACK:

To switch to a chord of the same type (from C Major/Minor chord to E Major/Minor chord), simply slide your hand over without moving the distance between your fingers.

The intervals are universal, so this will always work. Simply position your first finger on the root note of the chord you wish to transfer to.

» An extension of that hack is to switch from 1 chord type to a different one entirely (Major to Minor, or vice versa).

All you need to do, either when your hand is positioned properly or after sliding your fingers to the desired notes/chord, is move your middle finger down 1 semitone (half step) to go from a Major to a Minor.

To do the opposite (Minor to Major chord), simply slide your middle (2nd) finger up 1 semitone (half step).

You don’t have to know how to play piano to be a great producer, just nail down the basics of Music Theory!

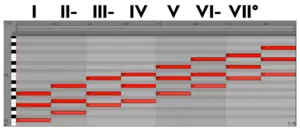

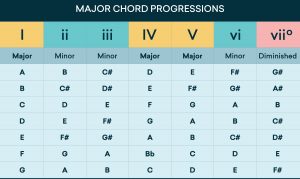

ROMAN NUMERALS

Even in today’s modern world, you will still see chords and progressions displayed as Roman Numerals.

They allow you to understand music on a more intimate level by diving into chord progressions, chord qualities, and chord inversions. It really brings to light how universal music really is, regardless of the scale in use.

In traditional Music Theory, Roman numerals (Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, Ⅳ, Ⅴ, etc.) represent both the degrees of the scale and the intervals contained within each chord.

- Uppercase Roman numerals (Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, Ⅳ, Ⅴ) represent Major Chords.

- Lowercase Roman numerals (ⅰ, ⅱ, ⅲ, ⅳ, ⅴ) represent Minor Chords.

Roman numerals are not exclusively tied to a particular scale. It’s not representative of which chord should be played, but rather what ‘degree’ of the given scale you choose, and its corresponding chord.

For instance, III denotes either the third scale degree or, more commonly, the chord built on it.

Regardless of the scale you choose, the degree intervals will be the same, and that’s truly all that’s important. Roman numerals can also be used to notate the chord progression of a song independent of key.

The standard twelve-bar blues progression (for example) uses the chords:

- I (first)

- IV (fourth)

- V (fifth)

So, you will sometimes see it written: I7, IV7, V7 since they are often dominant seventh chords.

IN THE KEY OF C MAJOR:

» The first scale degree (tonic) is C

» The fourth (subdominant) is F

» The fifth (dominant) is a G.

So the I7, IV7, and V7 chords are C7, F7, and G7. On the other hand, in the key of A major: the I7, IV7, and V7 chords would be A7, D7, and E7.

Roman numerals thus abstract chord progressions, making them independent of key, so they can easily be transposed.

NOTE: If it’s difficult to wrap your head around this concept, simply refer back to what we talked about earlier… Our brains recognize a song by the relationship between notes (Happy Birthday, as discussed) not the note it begins on.

PRO-TIP: Copyright laws do NOT apply to chord progressions. There are common strings of Roman Numerals used throughout music, usually tied to a certain genre. You will hear it over and over again.

Some parts are familiar, even on a subconscious level, which makes them desirable, simply due to variation and how the chord progression is applied and relates to the track. Knowing this will give you an upper hand.

» Next time you’re having difficulty determining a ‘starting off’ point:

- Do a quick google search for popular/standard chord progressions (let’s say gospel).

- Pick a scale

- Plug the chords into your piano roll

- See what happens!

From there, simply make alterations as you see fit (transpose and invert notes).

SAVE YOUR MAPS

STEP 1 一 Create a new midi clip with a specific length value. I suggest making it a bar-long before entering the piano roll. Consider the midi scale ‘map’ a visual guide, not a tool.

STEP 2 一 Map and stack all the notes within your scale on top of one another. It’s beneficial to bring the velocity of each note to 0 (once programmed). Be careful to not blow a speaker out though. If possible, have your clip assigned to nothing.

STEP 3 一 Map out the scale. Sure, you can go online and plug in the notes of any scale on top of one another, but if you really want to master Theory, use the chord codes to input these notes. Memorization is key here.

- Decide the key you want to compose in; let’s say, C Major.

- Input those notes, stacking them.

So, starting out at C, you should have ended up plugging in: C, D, E, F, G, A, and B.

I recommend drawing in the note to be quantized at the same length as the midi clip you’ve created. Now you can simply save this clip as a C Major map for later use and reference.

» Plus, you can use it as a universal Major scale map as well:

- To Switch to any Major scale (any of the 12 notes, including black keys), first select all the notes.

- Move the root note from C to any note you want to base your scale on.

If you slide the notes so the root note is now A#, you have successfully mapped out an A# Major scale. Easy, right?

It’s beneficial not only for later reference but for learning purposes as well. This can be done with any scale imaginable!

Set aside 15-20 minutes to make a preset/template ‘map’ for every common and uncommon scale type you desire. Again, It may seem pointless, but you will quickly see that’s not the case at all.

Since changing the root note of any given scale type is easy, just focus on making 1 scale map for each corresponding type. Like 1 Major, 1 Minor, etc.

Let’s say you wanted to make a dope Arabian trap beat but don’t know where to start…

Simply open up the Indian scale map/template you’ve created and compose accordingly. You will be able to see the notes within that specific scale and its unique structure.

You will even be able to see the tonal qualities that can apply to the notes played when using a synth/instrument/sampler, which allow you to load what’s known as ‘scala’ micro-tuning files.

If they are not available, you can usually adjust the fine-tuning manually for the intended effect.

» These ‘scala’ files do NOT change the scale you play in, but rather the tuning of each specific note.

Notes are, as previously mentioned, just arbitrary frequencies that we decided to build our music off of. A perfect C as we know it (in Western Music) may realistically be tuned differently, if only by a handful of cents.

Are you still confused about what a map actually is?…

Check out the FREE Unison Essential Famous MIDI Chord Progressions pack. You will have instant access to the equivalent of these scale maps, in virtually every chord imaginable.

Constructing chord progressions has never been simpler!

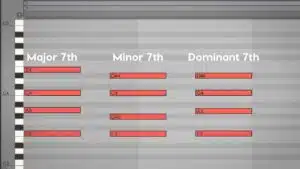

7TH, 9TH, 11TH, 13TH CHORDS

Extended chords have notes in addition to the basic triad, called Extensions (7th, 9th, 11th, 13th).

- 7th = triad + 7th

- 9th = triad + 7th + 9th

- 11th = triad + 7th + 9th + 11th

- 13th = triad + 7th + 9th + 11th + 13th

Technically, the 7th is not considered an extended chord, but for all intents and purposes, consider anything other than a basic triad to be an extended chord.

Just remember that all 7th chords can be extended and altered. These extensions are named based on the scale degrees, or ‘note numbers’ they belong to (in any given scale).

FOR EXAMPLE: When going from a C Major Triad to a C Major 7 Chord, the last (4th) note is 7 ‘scale degrees’ from the scale’s root note. The 9th is 9 degrees from the scale’s root note.

So, to get the 7th in a C Major 7, refer to the C Major Scale and count upwards until you reach the 7th scale degree (the 7th note in the C Major Scale).

- For Minor scales 一 the 7th is always 11 semitones from the root note, while the 9th remains 14 semitones away.

- For Major scales 一 a 7th is always 10 semitones from the root note, while a 9th is 13 semitones away.

That particular way of thinking can get confusing, especially if you’re first starting out.

So, for a foolproof method, simply look at the scale (with help from your Midi Clips, created earlier) and count upwards from the root note to the desired scale degree.

Sometimes you will see a C Major 9th Chord composed of only 4 notes (skipping the 7th), but normally the notes below it are played along with it.

- When creating a C Minor 9th 一 map out the C Minor scale and count to the 7th and 9th note within that specific scale. You will successfully get the correct note every single time.

- If you wanted to play an A# Major 7th chord 一 look at the notes within the A# Major 7th chord and simply take (or plug-in) the A# Major chord and count to the 7th note within the A# MAJOR scale to find the 7th.

This applies to all extended chords such as 12ths, 14ths, etc.

The Major/Minor scales contain only 7 notes. So, to find any value above 7 (9th, 11th, etc.), you must loop the scale around and continue counting UP that way.

YOU CAN DO THIS ONE OF TWO WAYS:

(A) When you reach the last note, loop back around to the root note.

(B) Select all the notes, duplicate them in your piano roll, and drag a copy to the octave above and below it. Assign the notes to match those of the original scale.

If you’re off by one note, everything can be destroyed and you’ll find yourself working on a completely different scale than intended.

DEFINITIONS TO BE FAMILIAR WITH:

- TRIAD 一 A chord made up of three notes/tones. Triads are the most common chords in Western music.

- DIMINISHED TRIAD (aka Minor Flattened Fifth) 一 A triad with a flattened (diminished) 5th. It encompasses more narrow intervals than the standard triad.

A Diminished Triad is more compact and offers an unexpected chord vibe with just the right amount of dissonance and tension needed to compose in certain situations. Or, when you just want to catch your listeners by surprise with an unexpected flip.

Remember, music and composition are so entrancing because of the build-up (tension) or dissonance, followed by a release/resolve.

If you have the same chord progression, but want to make the chord sound more ‘off’ for the last measure, this should be your go-to technique.

≫ BONUS TIP: ‘Flattening a note’ means to bring it down by just 1 semitone. I’m sure you can see the link between flats and sharps with this knowledge.

If you ever decide to add or include a Diminished Chord (or transform any existing chord into a diminished one), simply flatten the top note!

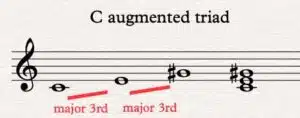

- AUGMENTED TRIAD 一 A chord made up of two major thirds. It is a major chord whose top note is raised by 1 semitone. Essentially the opposite of a diminished chord/triad. It is composed of notes that are spaced further apart, at wider intervals than those of a regular triad.

Again, this can also add a sense of dissonance and tension, providing a different/unique feel and vibe. Next time you want to hear what any given chord sounds like when augmented, simply bring up the top note.

Remember, in music production, sometimes the more ‘unconventional’ method sounds better than anything else. Don’t be afraid to bring any of the notes within a chord up or down by a semitone. You may discover some hidden treasures.

- KEY CHANGE 一 The change from one tonality (tonic, or tonal center) to another. Generally, it simply means the changing of your song’s scale.

This can be a simple transposition (from C Major to A♯ Major) or a total change in scale types, such as switching from an A Major to an A Minor scale.

- SCALE DEGREE 一 The position of a particular note on a scale relative to the Tonic. Useful for indicating the size of intervals and chords, and to determine whether they are Major or Minor.

Also, they are key when building extended chords and looking for the relative scale of any given scale. Theory revolves around the scale degrees, so this is a super important term to be familiar with.

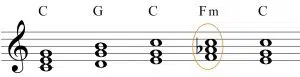

- BORROWED CHORD 一 a chord ‘borrowed’ from the relative scale; belonging to the scale that’s currently being used.

They are typically used as ‘color chords’ and provide harmonic variety through contrasting scale forms (such as Major and Minor Scales).

- RELATIVE SCALE 一 When referring to a ‘relative’ scale, it simply means the use of a scale containing the same notes, but not the same root note. Each Major scale has a relative Minor scale, and vice versa (they are the same).

The part that tends to cause the most confusion when dealing with this practice is the terms ‘relative scale’ and ‘parallel scale.’ They do NOT mean the same thing!

A Parallel Scale is a Major/Minor scale with the SAME tonic. For instance, D Major’s ‘Parallel Scale’ is D Minor.

![]()

- OCTAVE 一 In the diatonic scales (Major, Minor, and Modal) of Western music, the octave is an interval of 12 notes. Each instance of the same note (different pitch) on a piano occurs as an octave, and each octave doubles the frequency (in Hertz) of the one before it. It is one of the most common, easily-identifiable intervals in music.

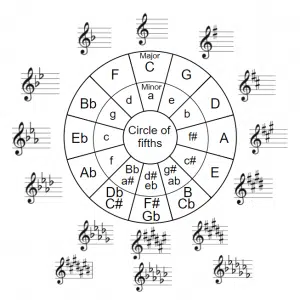

- CIRCLE OF FIFTHS 一 Reveals information about the progression of key signatures, how many sharps/flats are in a key, and their relationships (internally and externally). Think of the circles of fifths as the Music Theory color wheel.

It is the arrangement of the 12 notes of the musical alphabet (in a circle). Each note on the circle is a perfect 5th apart.

» It may seem intimidating, but all will be explained in our upcoming article, as part of this Theory Series.

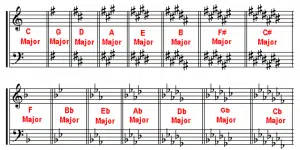

- KEY SIGNATURES 一 A symbol at the beginning of a song (usually found in sheet music) that defines the scale in use. To keep it simple, its main role is to tell you what scale the song was composed in. It contains essential information that musicians need when playing from sheet music.

Don’t confuse this term with ‘time signatures’ as those are also found at the beginning, or throughout a song (sheet music). They indicate the time signature of the song at hand.

- VOICE LEADING 一 The way in which individual voices move from chord to chord. The best voice-leading happens when all the individual voices move smoothly. To achieve this, simply move between chords using the same note, or move up/down a step in the inner voices of the chord (whenever possible).

For example: to go from a C Major to a C Minor. Then, go from a C Minor to an E Flat Major. Continue this cycle, inputting the next chord based on a note from the previous chord.

It is not ideal for every composition, but it’s certainly a cool trick to implement now and then. If you were to use it in every song, make sure it’s very subtle, and only reserved for select chords, or for some variation.

- CHORD PROGRESSION 一 A series of chords played in succession. The chords you use, and the order in which you play them make up the harmony of a song.

- MELODY 一 A collection of notes/musical tones strung together as a single entity. It’s almost always Monophonic, at least initially; before you add intermittent harmony and octave-stacks if desired.

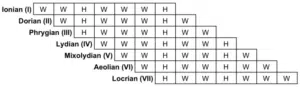

SCALE MODES

Modes are used as a way to reorganize the pitches of a scale so the focal point of that scale changes. In a single key, every mode contains the exact same pitches. By changing the focal point, you can access new and interesting sounds.

This has a similar concept as relative scales and can be viewed as an alternative version of the same scale.

THE 7 MOST WIDELY RECOGNIZED MODES:

- Ionian

This is the same as the Major scale. If you’re first starting out, this is the scale you would most likely learn first (the C Major Scale) as its diatonic notes all occur on white keys. If you already know this scale, you’ve mastered the Ionian mode already!

C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C (Ionian)

- Dorian (Russian Mode)

The second mode of the Major scale. The Dorian Mode is simply a Minor Scale with natural sixth and flattened seventh scale degrees. To build the Dorian mode, take all the pitches of the C Major Scale (C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C) and start from D:

D-E-F-G-A-B-C-D (Dorian)

- Phrygian

The third mode of the Major scale. The Phrygian mode is simply a Minor scale with a flat second, flat sixth, and flattened seventh scale degrees. To build the Phrygian mode, take all the pitches of the C Major scale and start from E:

E-F-G-A-B-C-D-E (Phrygian)

- Lydian

The fourth mode of the Major scale. It is a Major scale with a raised fourth scale degree. To build the Lydian mode, take all the pitches of the C Major scale and start from F:

F-G-A-B-C-D-E-F (Lydian)

- Mixolydian (Dominant Mode)

The fifth mode of the Major scale. This is a major scale based on the fifth scale degree of whichever key you are in at the time. It is bound up with chord progressions, especially between the tonic and dominant. You can find this mode in most forms of popular music today. The easiest way to build this particular mode is to take the pitches of the C Major scale and begin from G:

G-A-B-C-D-E-F-G (Mixolydian)

- Aeolian (Natural Minor Scale)

The sixth mode of the Major scale. It is based on the sixth scale degree of its relative Major scale. For instance, a C Major scale would take A Minor (relative minor) and all the white notes on the keyboard from A to A would constitute the A Aeolian Mode or the A Natural Minor Scale.

Many popular songs that were written in a Minor key make use of this mode, and if you’re looking to dip your toes in the compositional pool, this is a great place to start.

A-B-C-D-E-F-G-A (Aeolian)

- Locrian

The seventh mode of the Major scale. The Locrian mode is a Minor scale with a flattened second, fifth, sixth, and seventh scale degrees.

This mode is probably the least common, but it does possess an enigmatic character worth exploring. To build the Locrian mode, take all the pitches of the C Major scale and start from B:

≫ B-C-D-E-F-G-A-B (Locrian)

FINAL THOUGHTS

Don’t concern yourself with the construction of a chord!

There is an endless supply of pre-made chords and templates for you to build upon, and we have some of the most unique, professional best-selling options available in the industry, with our Midi Chord Packs.

They contain fully customizable, moldable, expandable, and collapsable chords unlike any you’ve ever heard. You will be provided with endless options in which to create your own masterpieces within minutes!

Download the FREE Unison Essential Advanced MIDI Chord Progressions here. Don’t just sequence your notes, sequence your chords.

Your music will instantly stand out, as you’ll have access to chords and progressions that takes YEARS of music theory experience to learn how to compose.

Part 2 of this Theory Series will cover everything you need to know about the Circle of Fifths.

Until next time…

40 Chord

Progressions

40 Chord

Progressions