Table of Contents

A song typically consists of/revolves around three main elements:

1. A percussive sequence (drums)

2. Melodic phrases (melody)

3. A set of chords (the progression)

4. Vocals

Depending on the order of which you produce music, you may consider one of these elements to be the foundation of your music. In the classical music sense, however, the chord progression is always used to drive the harmonic components of your song, and is the basis of the melodic series that your song follows.

For those of you who are fairly new to producing, ‘Theory’ may sound like a foreign or intimidating term, and the process may strike you as extremely daunting. Well… I’m here to provide you some comfort by informing you that the foundation of traditional Theory is, in fact, not as challenging as one might believe.

Before the modern implementation of MIDI, Theory involved reading and understanding actual notation in the form of sheet music and being able to successfully translate it to the instrument being used.

So, when referring to all the intricate rules and details that are involved in traditional theory, it can get very complicated… but when looking at Theory through the eyes of the modern producer (who utilizes piano rolls), it’s significantly easier to comprehend and master.

Truthfully, if you’re capable of assimilating a DAW, I’m fully confident you can grasp (or at least obtain a basic understanding of) the fundamentals within a number of hours.

Theory is truly the ultimate musical blueprint; designed to guide you through the laborious process of creating compositions from the ground up. Even though a vast majority of producers have the preconceived notion that it’s too ‘difficult’ for them to understand, or have a false representation of how steep the learning curve is (deeming it too onerous to conquer), it’s veritably simple. Coming from a production standpoint, even having what is considered minimal knowledge of the subject can benefit you greatly.

Plus, if you’re learning Theory strictly for production-related purposes (not composition), getting acquainted with elements such as staffs, symbols, notes, and things of that nature may not be necessary; saving you an abundance of time and energy.

Today I will be covering some of the basic principles of Theory, along with some more modern methods (often referred to as ‘hack’ or ‘producer theory’), that will help and enable you to create chords effortlessly… regardless of how far you decide to delve into ‘Theory’ as a whole.

I will also be discussing ‘Chord Codes,’ which is an extremely lucid, quick to administer, and effective method of creating chords. Plus, the only prerequisite is knowing how to count (no, seriously).

I will not, however, be going over every single intricate detail pertaining to the principles of Theory, but instead (for the purpose of rapid learning), I will strictly disclose the pivotal information that is required to accurately comprehend the essence of Theory. That way, you’ll be capable of making any and every Major or Minor basic triad chord (without having to concern yourself with said details) in absolutely no time.

IDENTIFYING, UNDERSTANDING, AND BUILDING MAJOR/MINOR SCALES

Before we get started, I MUST explain and clarify a very common misunderstanding: a Sharp (#) or Flat (b) is NOT determined by the color note of which you are currently playing (white or black), but rather it’s relativity to another note, the direction of the scale, and the action we are taking on the note (e.g., whether we’re bringing it up or down).

By making a note a ‘sharp’ (#), what we’re doing is raising it’s value; bringing it up.

By making a note ‘flat’(b), what we’re doing is lowering it’s value; bringing it down, and flattening it.

For example, if we took ‘G’ and brought it UP a semitone, it would then be considered G#; if we took it and brought it DOWN a semitone, it would then be considered Gb (flat).

People habitually think all the blacks keys are ‘sharps’ because typically (in practice) we go up the scale (ascend), not the other way around (descend). Having said that, everybody knows the black key next to C as C# BUT, if we were going down the scale (in reverse), the same note would actually be considered Db.

This piece of information is vital when it comes to conducting/producing music and, once you grasp the concept, it’s fairly straightforward.

NOTE: When dealing with ‘piano rolls’, or any variation of digital/MIDI notation in general, since the computer has a considerably difficult time differentiating between what is relative and what is not (in regards to the movement of the notes), Db will ALWAYS be identified as C#. So, from here on out, when categorizing any note as a ‘flat’, be cognizant of the fact that it will show up in your DAW as a ‘sharp’. For example… let’s say I lowered G by one semitone, bringing it to Gb (flat), it would represented as F# (sharp) in your DAW. Essentially they are the same note.

When it comes to modern music and ‘western’ music, it remains pretty consistent that most songs (pertaining to that genre of music) are typically written in either the Major or Minor scale. Having said that, songs that are written in other scales can sometimes create an exceptionally desirable sound, due to the fact that it’s not heard as often and our brains tend to be intrigued by new/previously unheard sounds or melodies; but for this lesson, let’s stick to the most popular, widely recognized, and frequently utilized patterns.

Chords are built from scales; all you really need to know is which specific scale you’re currently working with in order to build chords that will appropriately match the tone/feel of that particular song (the possibilities/combinations are truly endless).

A question that I commonly get asked is, what notes are in the Major and Minor scales? Well… truthfully, it’s a slightly complicated/tricky answer: all 12 of them.

With that said, only 7 notes are in any given (diatonic) scale at a time; the specific notes are determined by, and relative to, which unique scale you’re working with and your ‘root’ note (the first/bottom note in the scale, also referred to as our ‘Tonic’).

EXAMPLE: If you are in C Minor, the notes in the scale will certainly differ from D Minor, but the process of determining them remains the same (using the formula below) regardless of what your root note is.

Thankfully, A good amount of DAW’s now come equipped with tools (such as chord and scale helpers) that makes it appreciably easier to map these things out WITHOUT any memorization required.

Check out your specific DAW’s features (or manual) to find out if it provides one of these effectual tools. If it does NOT, the basic formulas and proper way to implement them are as follows:

First, we’re going to start by choosing any of the 12 notes within the chromatic scale; this will be considered your ‘root’ note.

REMEMBER: Both the Major and Minor scales each contain 12 basic triad variations that you’re able to pick from; one for every note in the octave range. Also, for future reference, keep in mind that every note in both the Major and Minor scale has a major and minor chord associated with it; more on that in the Unison MIDI Chord Pack, but first, let’s cover the basics.

We will use the letter ‘R’ to notate our root note.

‘W’ represents a ‘whole’ step. A whole step is the distance between two notes (consisting of two half steps/semi-tones); for example, from C to D. If you look at the keyboard, you’re able to notice that there is a note in between these two notes.

‘H’ represents a ‘half’ step. A half step is the distance between a note and the note directly next to it (also known as a ‘semitone’). For example, from C to C# (D flat).

Major = R + W + W + H + W + W + W

Using the formula, if we start at ‘C’, our notes would read as follows: C,D,E,F,G,A,B… giving us the C Major scale.

Minor = R + W + H + W + W + H + W

Using the formula, if we start at ‘C’, our notes would read as follows: C,D,D#,F,G,G#,A#… giving us the C Minor scale.

BUILDING CHORD TRIADS AND UNDERSTANDING INTERVALS

An interval is the difference between two pitches (notes); these intervals are determined by how far (in distance) each note is from one another. Look at each one as a half step.

By employing intervals, you’re able to easily and effortlessly assign landmarks (that tell you how far one note is from another note), which can help you to strategically discover new, creative chords or melodies.

NOTE: These intervals are not assigned by their relation to the scale, but rather, they are determined on a ‘note to note’ basis.

An interval of just 1 semitone is known as a ‘minor second’.

An interval of 7 notes (half steps from the root note) is known as a ‘perfect fifth’

Minor Second: 1 half step

Major Second: 2 half steps

Minor Third: 3 half steps

Major Third: 4 half steps

Perfect Fourth: 5 half steps

Augmented Fourth: 6 half steps

Perfect Fifth: 7 half steps

Minor Sixth: 8 half steps

Major Sixth: 9 half steps

Minor Seventh: 10 half steps

Major Seventh: 11 half steps

Octave (Unison): 12 half steps

These intervals can be categorized as either:

1. Melodic – when they appear as a sequence of consecutive notes (when two notes are played one after the other).

OR

2. Harmonic – when two related notes are played at the exact same time (as they are sequenced within a chord).

Taking these intervals and intricately stacking them on top of one another (and/or playing them in sequence) is the absolute foundation of every musical creation ever produced, regardless of whether it was strategically/consciously executed or not.

By intimately knowing, consistently referencing, and expertly administering these intervals, you’ll be able to successfully create chords and melodies that directly follow the rules of Theory (while simultaneously producing a pleasing and much desired sound).

Today, we’re solely focusing on Harmonic Intervals, as they are indeed the building blocks of a chord.

A chord is defined as any harmonic set of pitches that consist of two or more (usually three or more) notes that are played at the SAME time. In Western music, 2-note chords are referred to as ‘Modes’ and 3-note chords are referred to as ‘Triads’; from those triads, many extended chords can be manufactured.

NOTE: Extended Chords are chords that contain between 4-7 notes, but for the sake of gaining and achieving a basic understanding of this subject (in a relatively painless manor), let’s focus on the triads for now; we will cover extended chords a little later.

UNDERSTANDING SCALE DEGREES, THIRDS AND FIFTHS.

Like I previously stated… triads are built from 3 notes; each of these individual notes are considered a ‘degree’ (beginning with the root note as the 1st degree).

Let’s pretend we were working with the C Major scale:

C, our root note, would be considered the 1st degree (also known as the ‘Tonic’).

D – 2nd degree (Supertonic)

E – 3rd degree (Mediant)

F – 4th degree (Subdominant)

G – 5th degree (Dominant)

A – 6th degree (Submediant)

B – 7th degree (Leading tone)

Keep in mind that these names/degrees apply to all diatonic (7 note) scales.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Degrees differ from Intervals, as they are a representation of the notes within a scale, whereas Intervals denote (indicate) semitones/half steps.

Now, building a a Major chord from any of these scales is exceedingly simple.

A Major triad consists of, again, 3 notes:

1. The Tonic (also referred to as the Root note).

2. The scale’s third (the 3rd note or degree within the scale from your root note/tonic). This is actually 4 semitones/half steps away from your tonic, as 4 intervals is considered a ‘Major Third’.

3. The scale’s fifth (the 5th note within the scale from your root note/tonic; the dominant). This is actually 7 semitones/half steps from your root note, as 4 intervals is considered a ‘perfect’ fifth.

These three notes are the basis of every basic major triad, and most chords are essentially just different variations of this structure. Move up and down freely, between all 12 semitones, and it stays the same; you will always be playing the Major triad.

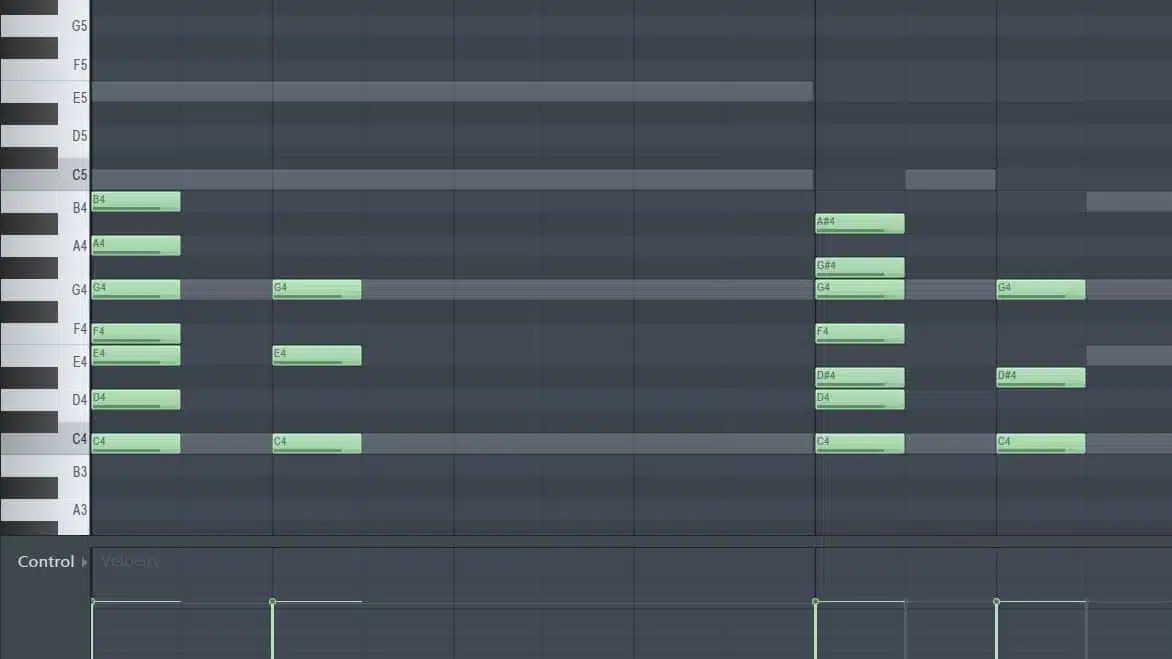

The same goes for the Minor triad, except the intervals change slightly. If we mapped out the Minor scale, the Minor triad would still consist of the tonic, the third, and the fifth. It may be easier to visualize by looking at the snapshot below…

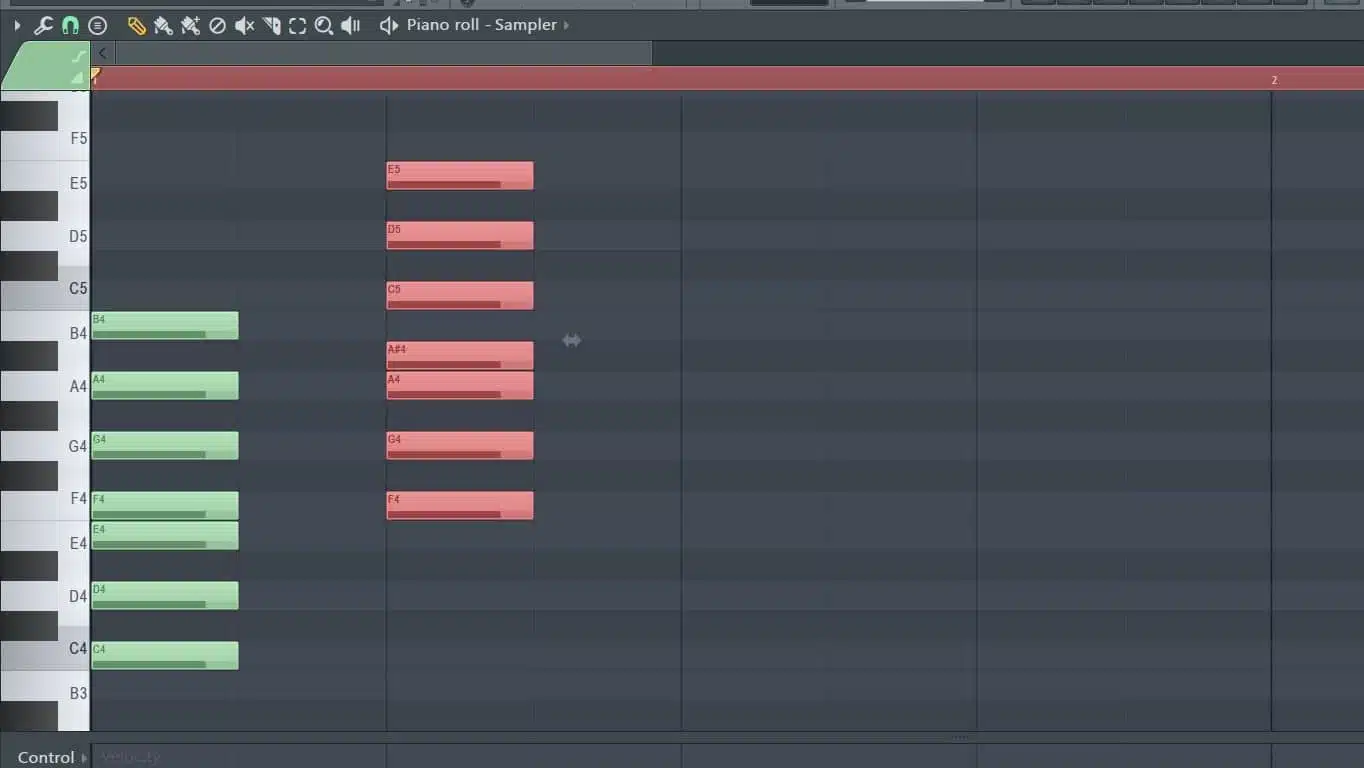

On the left… the C Major scale is mapped out in the piano roll, with it’s C Major triad next to it.

On the right… is the C Minor scale mapped out, with the C Minor triad beside it.

Notice how the chords only differ by 1 note; although the Minor chord is flattened, it still remains the ‘third’ note in the minor scale. This is why 4 steps (intervals) is called a Major or ‘perfect’ third, and 3 steps is called a minor third. When an interval is perfect, it typically means it’s the Major variation.

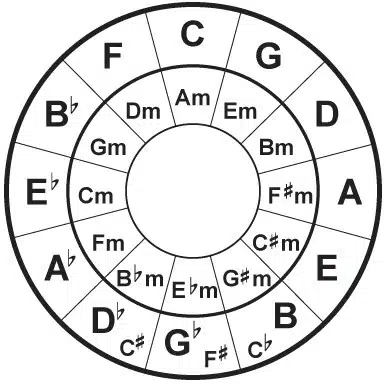

I’m fairly certain that you’ve heard of the ‘Circle of Fifths’. If you haven’t, it’s a sequence of pitches/key tonalities, represented as a circle, in which the next pitch (turning clockwise) is found seven semitones higher than the previous one; indicating that keys’ fifth. This will also provide you with some creative options for a key change, even if it’s a few tones over.

The further around the circle you go, the more disparate and unrelated the keys become from one another. Keep in mind that many variations of this table has been made (for many purposes), and identifying a given note’s/key’s fifth is just it’s original/primary function.

You can also use the chart below to find your Major keys relative Minor key (the notation inside the circle); this is essentially the same chord (as it contains the same notes) except the tonic has changed.

NOTE: This concept/topic is expertly covered (in-depth) within the documentation of the Unison MIDI Chord Pack. So, if you wish to expand your knowledge of this subject, or more traditional aspects of Theory (including the Roman Numeral Chord Sequencing System), I highly suggest you check it out – it’s phenomenally written and detailed!

- The outer circle contains the Major scale

- The inner circle consist of the Minor scale

In my personal experience, I have found that charts like these are exceptionally beneficial (especially when first starting out) because they help you to visualize the process of which you’re attempting to acquire. The circle’s design is also conducive to composing/harmonizing melodies, building chords, and modulating different keys within a composition.

Another reason why utilizing these charts are considered supremely advantageous is because every chord has a driving force (generally, the root note), and by knowing/being familiar with the fifth of ANY given note, you’ll be able to easily decipher which chords will fit best next to one another; making the structure of your song’s composition and progression more of a calculated/mathematical decision, as opposed to randomly predicting. Plus, the process of figuring it out then becomes much quicker, and significantly less daunting.

NOTE: It is also an amazing resource to take advantage of when trying to decipher which note should be played next in a given melody; making things really come ‘full circle’. Memorizing these diagrams will not only speed up your process/work flow, but ultimately leads to you undergoing a more fluid, intuitive songwriting process. So, in my opinion, it’s WELL worth it to invest some time in thoroughly delving into this subject, as the perks are endless.

Breaking it down

Our C Major scale is comprised of the following 7 notes: C, D, E, F, G, A, B.

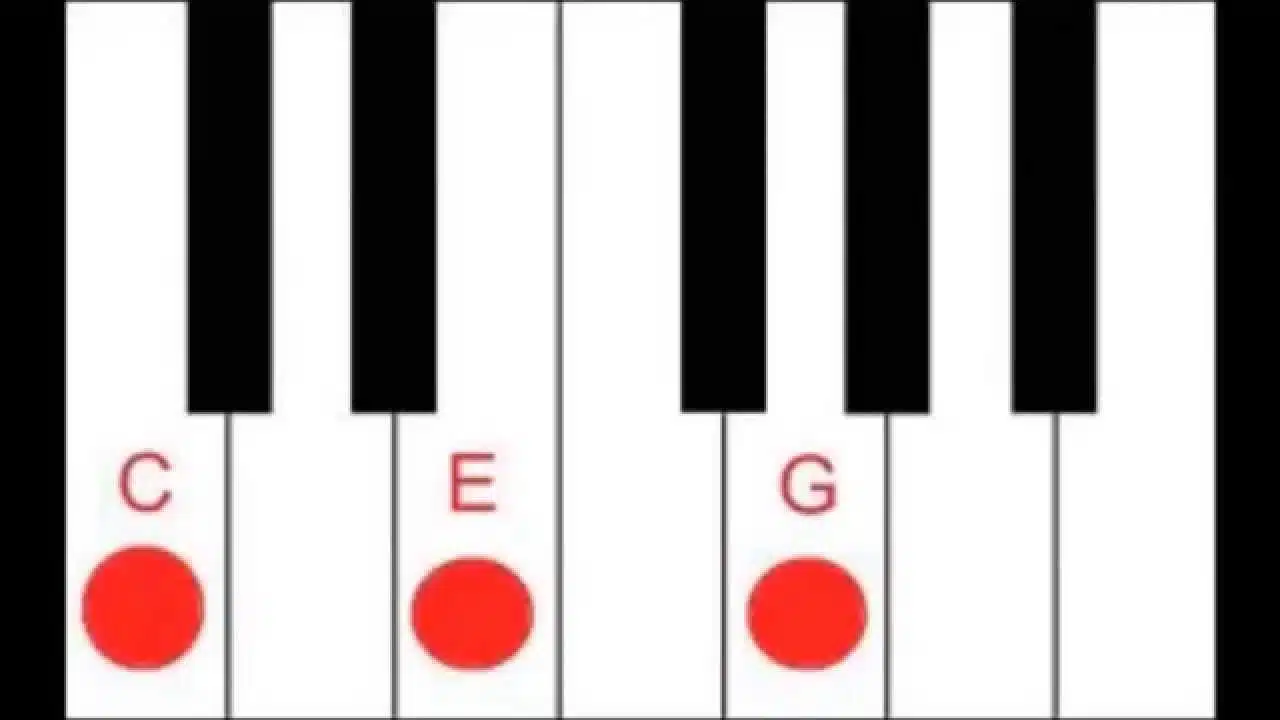

How do you find the third and fifth? Well, you simply count… starting with C (the root note) be represented as #1; the 3rd note would be ‘E’, and the final note in the sequence (the 5th) would be G. So our C Major triad is… C, E, and G.

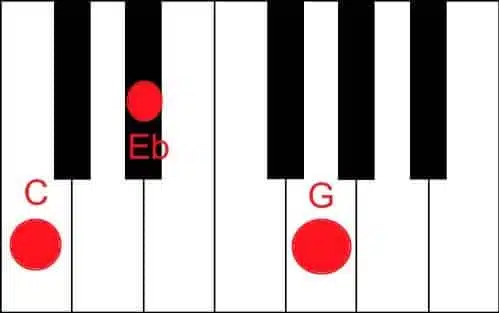

To achieve your C Minor chord triad from a Major scale, you merely take the E and flatten it; bringing it down to Eb (or D#). That lowercase ‘b’ stands for flat, or flattened. When we’re told to ‘flatten’ a note, it solely means to lower (or, bring down) the note ONE semitone/half step.

There you have it, you’ve just successfully created/deciphered both the basic C Major and Minor triads!

Now, utilizing a piano roll when attempting to change like-scales is easy, and I urge you use one (at least in the beginning) so you can accurately visualize how interconnected everything truly is.

Simply map out the notes of a C Major, and transpose ALL of them until your root note is at the desired location. If you want an F Major scale, map out the C Major scale and transpose it up to F.

Conversely, you always have the option of starting at F and using our ‘major’ formula but I have found that, when building chords, it’s much easier to do it this way.

To achieve a Minor chord, simply map out a Minor scale of your choice, then use the following formula: 1-3-5. In other words, the tonic, the third, and the fifth.

To map out a Major chord from a Minor scale use the formula 1-3-5 (first, third and fifth) and raise (augment) the third by one note.

NOTE: Any Minor-chord triad is essentially the same as a Major-chord triad EXCEPT the 3rd (or ‘middle’) note is brought DOWN 1 semitone, and flattened.

The same principle applies when wishing/attempting to take a set of Minor chords and turn them into a set of Major chords (only, reversed); simply bring the 3rd note (technically, the 2nd or ‘middle’ note in the chord) UP a semitone.

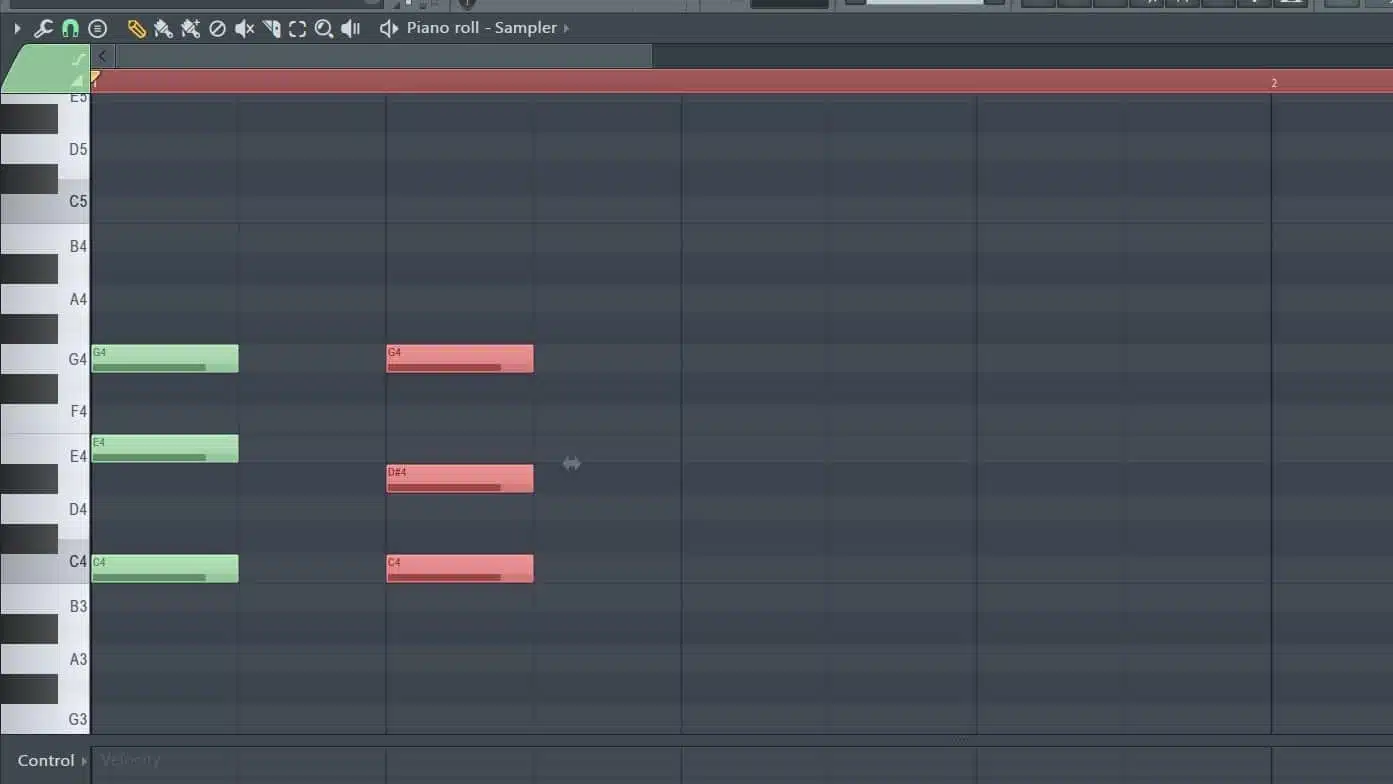

On the left is the Major triad.

On the right, the Minor triad.

TIP: If you find yourself creating a progression with ALL Major and Minor chords (like I sometimes do), execute some trial and error to determine which ‘type’ you want each chord to be.

You now know how to properly (and quickly) take a Minor chord and turn it into a Major chord, and vice versa, so don’t be hesitant/scared to swap them out and experiment a little; it can make a huge impact on the progression and the overall feel of the track or sequence..

Hopefully this way of visualizing things will make it slightly easier to comprehend:

Breaking it down

– When dealing with the Minor scale, the third is always 3 notes (or, 3 half steps/3 semitones) away from the root note.

– When dealing with the Major scale, the third is always 4 notes (or, 4 half steps/4 semitones) away from the root note.

– In order to discover the fifth, for both the Major and Minor scales, simply remember that it’s always 7 half steps/semitones from the root note; this is where being knowledgeable of intervals come into play.

NOTE: This way of thinking is where ‘Chord Codes’ originate from, and is what we’re discussing (in-depth) in the Chord Codes section.

Now that you are fairly familiar with the process of identifying any given scale’s third and fifth (and where they are located in relation to the root note), you can now take this information, and apply it, to build any triad imaginable within the Major or Minor scales.

NOTE: I must emphasize that the Unison MIDI Chord Pack has some key variations of extended and inverted chords; serving as a great resource to reference if wishing to apply the aforementioned knowledge yourself.

DIMINISHED CHORDS

Moving forward… when dealing with Major and Minor triads, the 2 alterations of these chords that commonly come up are: Diminished and Augmented.

Major chords tend to sound ‘happier’ than minor chords, which are normally associated with a more ‘sad’ sound.

TIP: Play a few variations on your own to get a better feel for/understanding of the differences in sound and feel that each chord exudes before attempting these exercises.

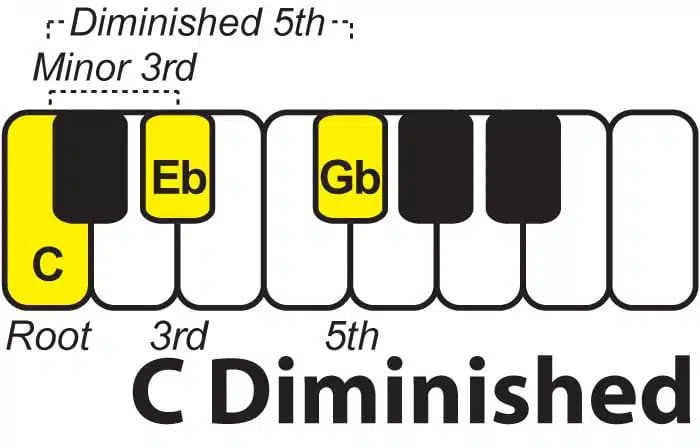

A diminished triad chord is characterized as a chord where both the third and fifth have been flattened. Technically, this works out to be a chord where each note is 1 1/2 steps from one another (starting from the root note); making each note 3 semitones apart.

To produce a diminished chord, simply take any Minor chord and flatten the fifth and, when dealing with a Major chord, simply flatten both the third and fifth.

EXAMPLE: Since a C Minor triad is C, Eb (D#), and G… then the diminished C Minor chord would be C, Eb (or D#), and finally Gb (or F#); having flattened both the third and fifth.

Minor and ‘diminished’ triads are also closely related; the difference is that the diminished triad has a diminished (flattened) fifth on top, whereas the minor triad has a perfect fifth.

Since minor chords are considered sad, diminished chords could be described/categorized as even sadder. They also give the illusion that they’re ‘leading up’ to a climax; you’ll never be under the impression that it’s finished or has completed a resolution.

Minor chords, by contrast, can be utilized as ‘passing’ chords, but can also stand strong as a final chord in a progression.

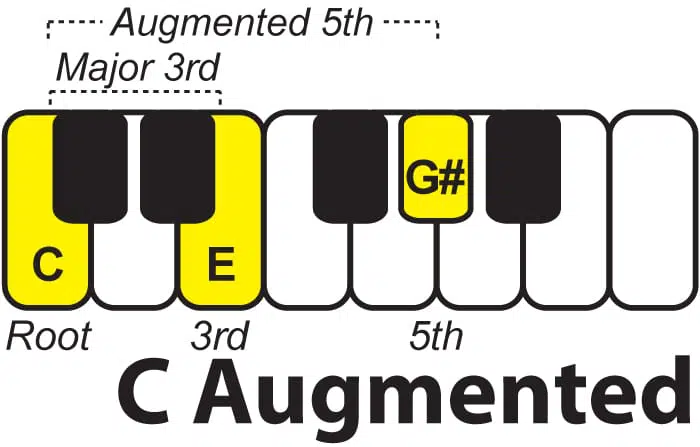

AUGMENTED CHORDS

An augmented triad chord is a Major chord with it’s 5th (top note) raised, or ‘augmented’ (hence it’s name). Augmented triads have an unusual, intriguing, mysterious sound, while diminished chords have an unsettling, dissonant sound.

EXAMPLE: Since a C Major triad is C, E, and G… an augmented C Major chord would be C, E, and finally G# (Ab); having raised/augmented the 5th.

Although the diminished and augmented chord types are utilized less frequently, that does NOT mean you should skip getting acquainted with them. When building a progression, It’s perfectly acceptable to strictly use standard Major or Minor chords… but that can get boring, fast.

By properly implementing one of these special chord types, you’ll have the freedom to experiment with the progression and bring extraordinary contrast to the table (unlike that of which you’d achieve if you hadn’t used it).

Having said that, these two particular chord types are not very interchangeable with each other (unlike the standard major and minor chords types), and deciding to include one of these chords at random may not yield such good/desirable results.

TIP: I highly suggest you create your progression using Major and Minor chords THEN proceed to strategically swap one out for either a Diminished or Augmented chord (of the same note and chord type).

For instance, if swapping out a C Minor chord for a Diminished, make sure it’s a Diminished C Minor chord and NOT a D. Although a D minor Diminished may sound adequate, the odds that you’ll get it right every single time is severely against you, so (for now) keep it simple and only swap out like-chord types.

Once you masterfully comprehend (and feel comfortable with) these concepts, by all means, feel free to break the patterns/mold… but when first starting out, it’s not worth the hassle and frustration.

They usually fit best second to last of a 4-8-chord progression, and tend to sound great for ‘wrapping things up’ (before the ‘resolution’); making things come together.

They don’t, however, sound particularly good when placed at the beginning (for the most part), and almost never serves any justice as the 1st chord in a progression. Again, do some experimenting and see where exactly in your progression they fit best.

Remember, trying to arbitrarily incorporate these chord types (and actually yielding desirable results) typically requires some experience/advanced knowledge, but if you feel like your progression is lacking something, it just might be one of them. Music is all about tension and release; dissonance is not always a bad thing, it just needs to be implemented correctly and ‘resolved’.

A Resolution is the move of a note/chord from a dissonance (or, unstable sound) to a consonance (or, more final, stable sound); in other words, when going from your scale’s dominant BACK to your root note.

Instead of playing the dominant chord as the second to last (in a progression) and wrapping it up with our Tonic, we can instead swap out the Dominant chord with an Augmented or Diminished of the SAME chord type. Again, this won’t always sound quite right, but when it’s appropriate/fitting, your ears will undoubtedly let you know.

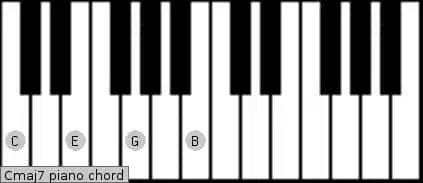

EXTENDED CHORDS

Extended chords are simply chords containing between 4-7 notes and, although a vast majority of chords used in modern music are built from triads, more often than not you’ll notice at least one section of a song that consists of these advanced chord types; most of jazzy/classical music is built from these chords.

By mastering these chord types (and, in the future, manipulating them), you’ll be able to successfully achieve a fuller, more advanced/dynamic progression; the 7th, 9th, 11th, and 13th chords are examples of extended chords.

To successfully create a Major 7th chord, simply add a 4th note (that note being the 7th note in the scale).

If C, E, and G is our C Major triad, than our C Major 7th would be C, E, G, and B (having added the 4th note).

To successfully create a Minor 7th, however, we apply the same process that we regularly would when dealing with Minor chords, and flatten the 7th; bringing it down 1 semitone to Bb (A#).

If you happen to be wondering how you’re supposed to get anything above the 7th when there are, in fact, only 7 notes in the Major and Minor scale… it’s simple.

As you know, every single note in the scale is considered a ‘degree’ so, in order to create a 9th chord, merely locate the scale’s SECOND degree and play that note in the octave range ABOVE it.

If we were to double up on our scale, we’re able to see that when we circle back to the 2nd degree, it’s actually the 9th chord in the scale.

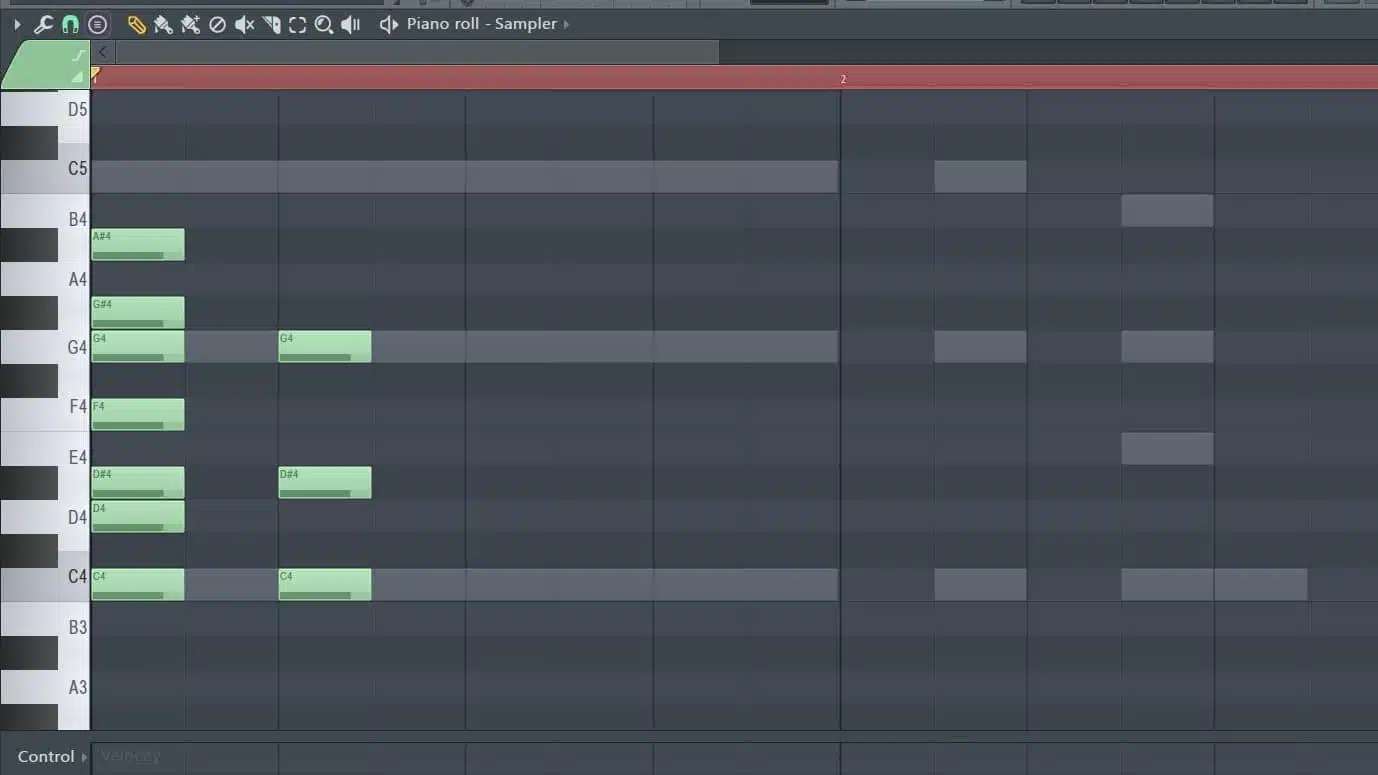

Below is the C major scale mapped out and doubled. This way, I am able to build my chord based on counting the intervals; a very common modern approach to MIDI/piano roll-based composition.

When we refer to the 7th, 9th, 11th, and 13th chords, we’re purely referring to the scale degrees. Since we only possess 7 notes in any given (Diatonic) scale, to achieve our 9th (or above), just continue counting UP; venturing into the next octave range.

EXAMPLE: If you were working In C Major, and playing C5, C6 would then be your 8th degree; continue with this sequence to reach higher/more complex chords (D6 being our 9th degree, and so on).

Realistically, these chord structures can be manipulated in an endless amount of ways and are WAY too many variations, concepts, and techniques to cover in this article alone; so I am going to leave off here (for now). In part two, I will be discussing (in-depth) the more complex/complicated chord structures and how to properly apply them to your own ‘chord progression constructions’.

I’m confident in the fact that, after reading this, you’re now equipped with the skills to understand and implement the fundamentals (or, building blocks) of any/every modern song.

CHORD CODES – THE THEORY HACK

Recently, due to many infuriating rules and intricacies regarding traditional theory, a new method has been devised to make the process of creating any Major or Minor chord considerably easier, called ‘chord codes’.

NOTE: If you wish to acquire more information/details on the subject of classical theory, and the traditional ways of implementing it, the Unison MIDI Chord Pack‘s PDF is an extremely well-written, in-depth, easy to comprehend guide to reference; containing all the basic principles (including various techniques on how to build many different types of chords).

For the sake of responding to the masses’ constant demand (who wish to immediately begin building chords by the memorization of a few, simple ‘codes’), however, I decided to include this subject. Trust me, you’ll thank me later.

The truly advantageous factor of chord codes is that they are completely interchangeable and, if you choose to use them, you can successfully build a complete song from scratch.

Be cognizant of the fact that chord codes are absolutely NOT used to replace (or suffice as a ‘real’ understanding of) Theory, but instead serve as a tool or ‘cheat’ when attempting to create chords rapidly, painlessly, and without possessing much knowledge of the subject.

0 is ALWAYS our starting point (the first note in the chord), and is referred to as the ‘root’ note/tonic. From that point forward, we count upwards; including/counting both the white and black keys as we go.These codes are universal regardless of your starting point..

The Major chord triad: 0-4-7

The Major 7th chord code: 0-4-7-11

EXAMPLE: If we start C… the next note in the chord will be E, then G, and lastly B

The Minor chord triad: 0-3-7

The Minor 7th chord code: 0-3-7-10

EXAMPLE: If we start at C… the next note in the chord will be D Sharp, then G, and lastly Bb (A#).

The same exact sequence should always be applied REGARDLESS of which note you start on.

The Diminished triad chord code: 0-3-6

The Diminished 7th code: 0-3-6-9

The Diminished Major 7th code: 0-3-6-11

The Augmented Major triad chord code: 0-4-8

The Augmented 7th chord code: 0-4-8-10

The Augmented Major 7th chord code: 0-4-8-11

Many universal codes exist, and a lot of good content has been written on this subject.

LAST WORDS

Our ears and brains have habitually served as prime indicators for detecting whether or not a sound is desirable and/or alluring… so trust them! However, in certain circumstances, breaking the rules can result in exemplary sounds (and can serve as a unique technique all in itself).

I sincerely urge you to experiment with your sounds by going against the grain, but remember to be cognizant of your boundaries and cautious not to stray too far off the beaten path.

People naturally enjoy/are drawn to sounds they are ‘familiar’ with (consciously or subconsciously), and tiny variations of these Major and Minor chords are primarily all we’re accustomed to in western music.

Due to repeatedly hearing different variations of the same core chords all our lives, our brains tend to expect and anticipate what chord is ‘supposed’ to come next in the sequence and even gets disappointed (or thrown off) if it’s mistaken. With that said, at times, an unexpected change can also be received as pleasing… if executed correctly, of course.

NOTE: Music is all about achieving and producing sounds that are aesthetically pleasing; satisfying both the ears and the brain (subconscious) equally. When you’re creating these progressions, be sure to maintain an ideal/healthy balance between the expected and unexpected chords; remaining cautious not to venture too far in either direction.

In Part 2, I will also be comprehensively discussing creative way to stylize your chords, as to make ANY progression genre-appropriate. Now that I have divulged all the onerous/arduous details, I sincerely hope you have a much better understanding of the foundation of any given song: the chord progression.

Trust me, I’m truly sympathetic towards those of you first learning this subject, as it can appear seemingly insurmountable and unconquerable, but I promise… once you acquire a basic knowledge of the fundamentals/basics, you’ll forever be thankful that you did (and probably end up laughing at yourself for ever being so apprehensive in the first place).

Now that you know the basics, the next step is learning the complexity of chord structure, inversions, the roman numerals to identify chords and how to apply them to your song.

The Unison MIDI Chord Pack’s PDF will go more in-depth on these topics among other I did not discuss. It’s essentially is a MIDI toolkit with over 1200 carefully-selected MIDI files that you can drag and drop into your own tracks, instantly creating a progression without having to build each chord from scratch. Once you have a full understanding of how chord progressions are built many doors will start to open. Check it out here

As always, if you’re experiencing any difficulties, or have any questions/comments, I’m here for you, anytime. Hope you enjoyed…

If you have any chord tricks or techniques that you wish to be included in Part 2… drop a comment below!

3 comments

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.

Quality!! I loved this, will be putting it into use ASAP

Great stuff!! A really good first grasp for a beginner learning the fundamentals!