Scale degrees are the individual notes that make up a scale 一 helping your melodies go crazy and your chord progressions super interesting.

And, if you’re going for a specific vibe/mood, they can help bring it to life.

Plus, understand the relationship between key signatures, scales, and chords, which is essential for creating music that brings killer emotions to the table.

As producers, knowing music theory basics like this can really help you lay down, improvise, and arrange your beats like a boss.

That’s why I’m breaking down everything you need to know about scale degrees, including:

- The basics of major and minor scale degrees ✓

- How scale degrees affect melody and harmony ✓

- The roles of the 7 scale degrees ✓

- How to use harmonic vs. melodic minor scales ✓

- Ways to build strong chord progressions ✓

- Tips for creating catchy melodies using scale degrees ✓

- Understanding key signatures ✓

- How to use relative scales to shift between keys ✓

- Advanced tips for mastering scale degrees ✓

- All the different elements you’ll need to know ✓

- The definition of a scale degree name/scale degree number ✓

- Pro techniques for integrating scale degrees in your music ✓

- Much more about scale degrees ✓

After today’s article, you’ll know all about scale degrees and how they can transform your approach to music production.

This way, you’ll seriously enhance your music theory skills, learn how to write better melodies, and build more cohesive progressions.

As well as structure your tracks like a true professional.

Plus, you’ll gain the confidence to move between key signatures, experiment with different scales, and create songs with intention and ultimate precision.

Table of Contents

- What are Scale Degrees?

- The Structure of Scales: Breaking it Down

- Major Scale Degrees

- Minor Scale Degrees

- Breaking Down the 7 Scale Degrees (In Detail)

- First Scale Degree (Tonic): The Root of All Harmony

- Second Scale Degree (Supertonic): Adding Tension & Color

- Third Scale Degree (Mediant): Establishing Major or Minor Tonality

- Fourth Scale Degree (Subdominant): Building Pre-Dominant Tension

- Fifth Scale Degree (Dominant): Creating Resolution & Drive

- Sixth Scale Degree (Submediant): Exploring Subtle Changes in Mood

- Seventh Scale Degree (Leading Tone): Leading Back to the Tonic

- Advanced Scale Degree Tips, Tricks, & Techniques

- Pro Tip: And What are Key Signatures Exactly?

- Key Concepts and Variations in Scale Degrees

- Final Thoughts

What are Scale Degrees?

In the simplest terms, scale degrees are the individual notes in a scale, each representing a specific function and feeling within that scale.

Think of them as the building blocks of music 一 guiding how melodies, harmonies, and basslines come to life across different keys and genres.

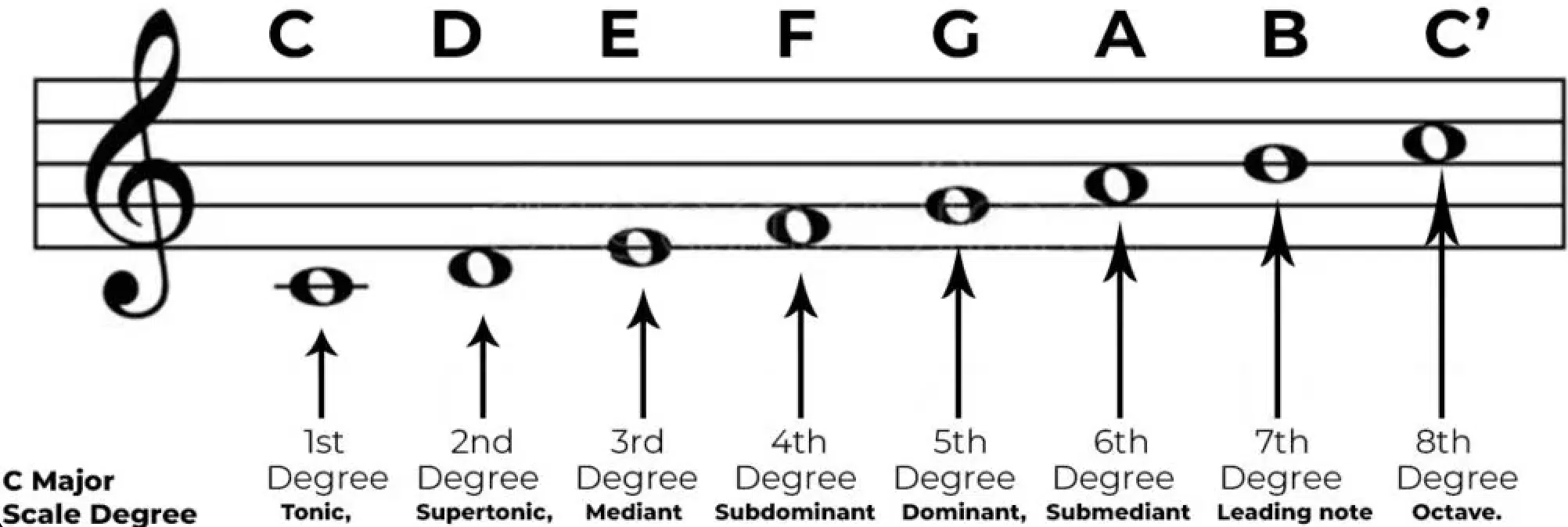

For example, when you play a C major scale, each note (C, D, E, F, G, A, B) has a specific scale degree that shapes the character of the music.

These scale degrees range from the first scale degree, aka the tonic, to the seventh scale degree, known as the leading tone.

In this case C would be the tonic and B would be the leading tone.

Understanding the unique role of each degree can help you create more dynamic melodies, powerful chord progressions, and flawless arrangements.

By mastering scale degrees, you can better control your music theory, unlock creative potential, and elevate your productions to a professional level.

Don’t worry, we’ll break down everything you need to know throughout the article so you really get a solid understanding of their power.

The Structure of Scales: Breaking it Down

Understanding scale degrees all starts with knowing how scales are built from the ground up.

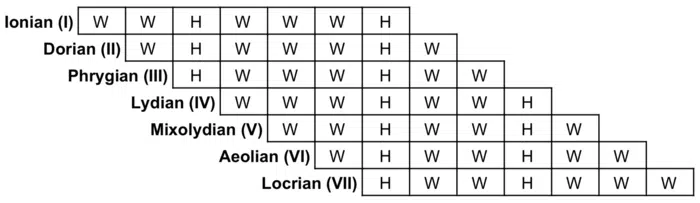

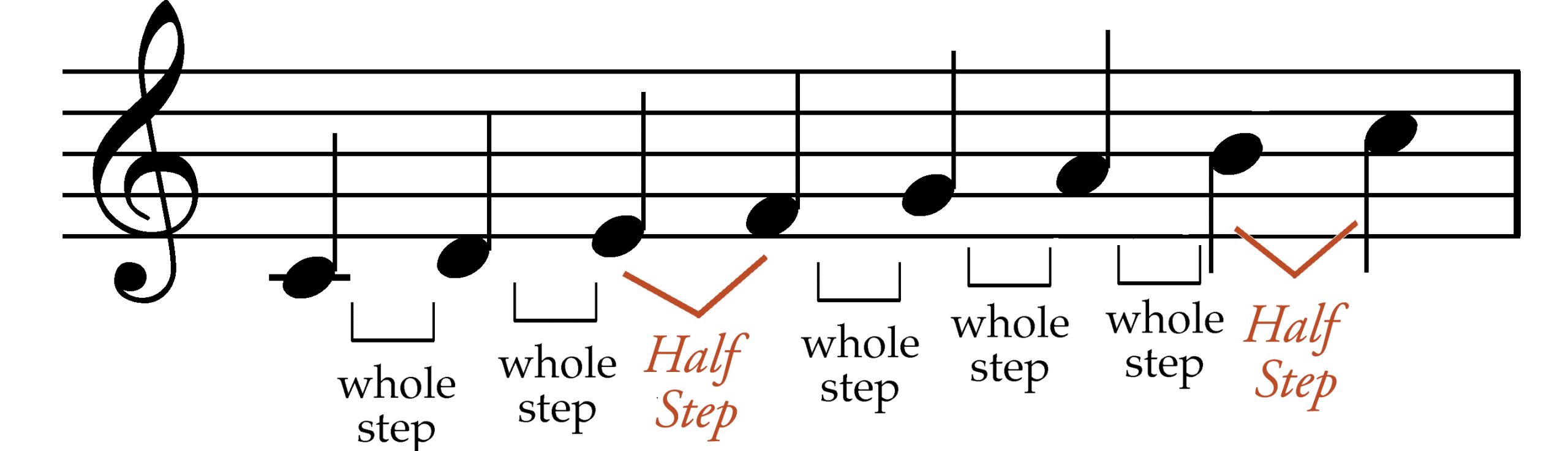

In a major scale like the D major scale or C major scale, you’ll follow a clear sequence of intervals (whole steps and half steps):

- Whole-step

- Whole-step

- Half-step

- Whole-step

- Whole-step

- Whole-step

- Half-step

For example, as you play the C major scale — C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C — you’ll see that the third scale degree (E) sits three half-steps above the tonic note (C).

A natural minor scale, on the other hand, has a slightly different feel, with lowered third, sixth, and seventh scale degrees.

So, if you switch to a C natural minor scale, you’ll be playing C, D, E♭, F, G, A♭, B♭, C.

These subtle changes in half-steps and whole steps create the distinct sounds of major and minor scales.

It’s the key to determining, and successfully conveying the overall vibe of your melodies, chord progressions, and even basslines.

Truly understanding these differences will help you master your decisions when it comes to key signatures so you can nail the specific mood/vibe you’re aiming for.

Major Scale Degrees

Major scale degrees (like the D major scale) create the bright, uplifting sound that characterizes major keys as a whole.

#1. In a C major scale, each scale degree has a specific role, starting with the first scale degree (C), which acts as the tonic note and provides a ‘home base’ I like to call it.

And yes, I’ll be using the C major scale as an example most of the time because it’s considered to be the easiest to work with and I don’t want my newbies left out.

For example, a simple progression like I-IV-V-I (C-F-G-C) feels complete because it starts and ends on the same tonic.

#2. The second scale degree (D) serves as the supertonic, which adds unmatched tension that often leads to the dominant or back to the tonic.

You’ll notice this in progressions like ii-V-I (Dm-G-C), where the supertonic (D) pushes the music forward.

It creates that sick sense of urgency that makes the dominant chord (G) feel powerful.

#3. The third scale degree (E) establishes the major tonality, laying down a happy tone when used prominently in melodies.

A bunch of classic pop melodies start with the third degree… It’s an easy way to add brightness and clarity to your tracks.

#4. The fourth scale degree (F), known as the subdominant, creates pre-dominant tension that typically resolves to the dominant (G), which is the fifth scale degree.

In a chord progression like IV-V-I (F-G-C), the subdominant (F) builds suspense for a super strong ending.

#5. The fifth scale degree (G) is all about creating strong resolution in chord progressions 一 pulling melodies back to the tonic a lot of the time.

You’ll hear this in many rock and EDM tracks, where the fifth degree sets up the perfect return to the home note, giving your listeners that satisfying sense of closure.

#6. The sixth scale degree (A), or submediant, adds emotional color, which makes it absolutely perfect for adding subtle shifts in mood.

You might hear this in lo-fi beats, where the submediant is used to introduce a touch of sadness without fully shifting away from the major key altogether.

#7. Finally, the seventh scale degree (B), called the leading tone as we covered, creates anticipation and leads the listener back to the tonic when it comes to the major scale.

So, as you can see, each scale degree has its own vibe and function, adding something to the distinct sound of the major scale.

TIP: For a more dynamic melody, try starting phrases on the third or sixth scale degree, as they can introduce different flavors without shifting the overall key.

Side note, if you want to learn absolutely everything about the major scale and its essence, with specific breakdowns and pro tips, we got you.

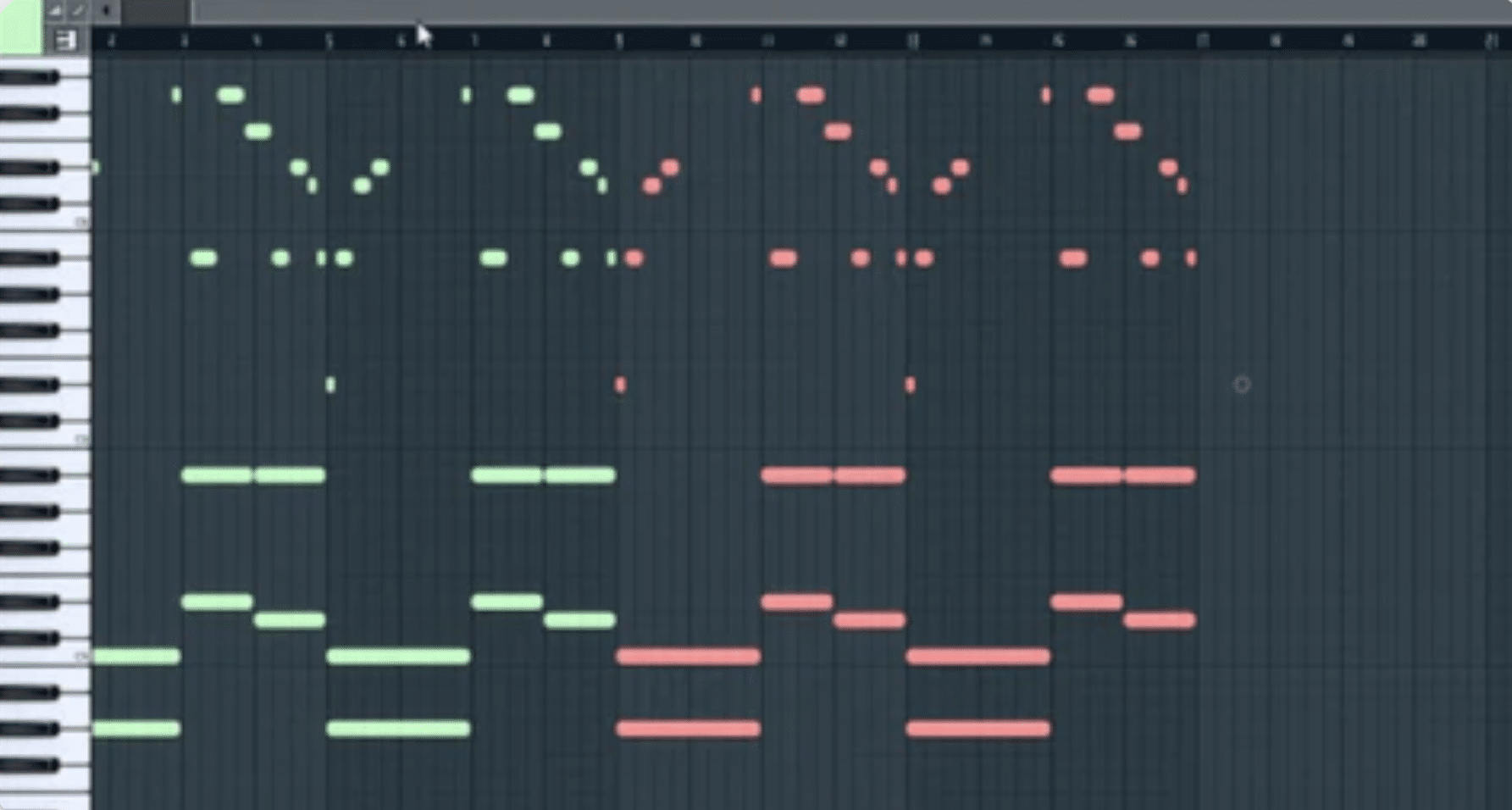

Minor Scale Degrees

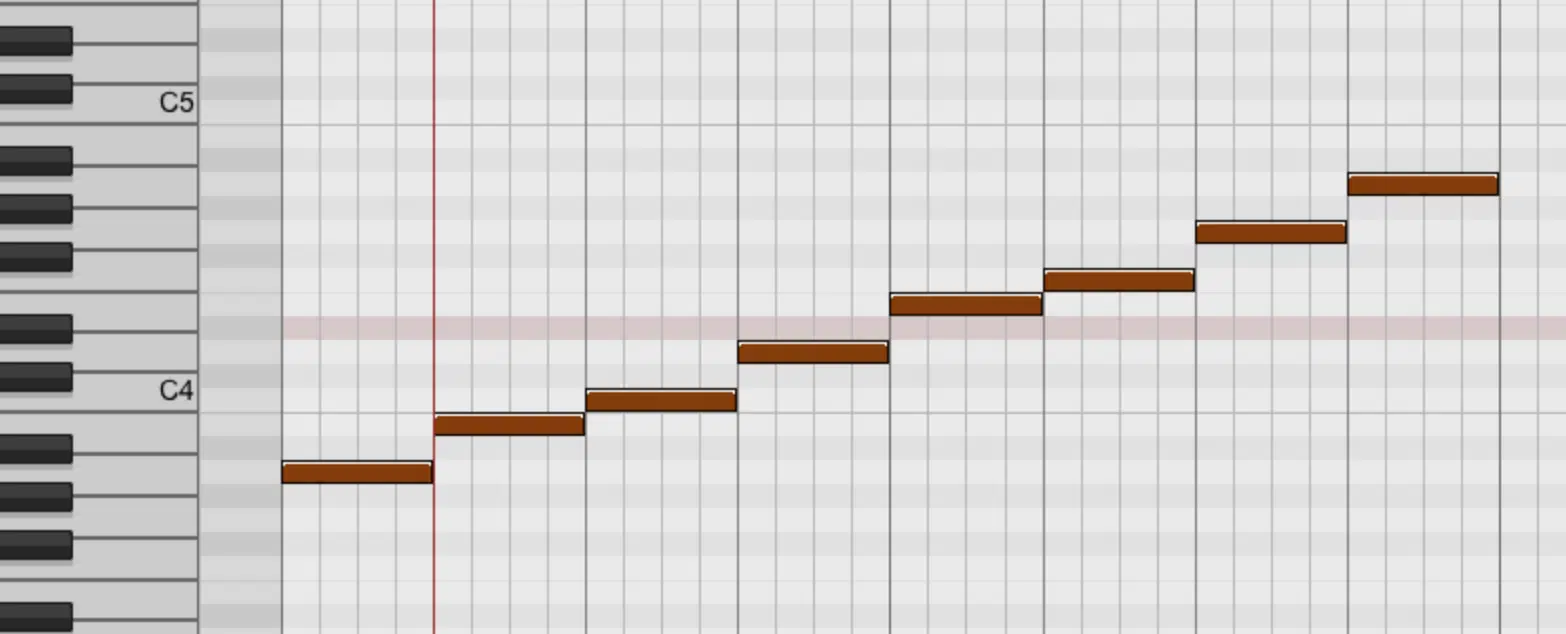

A Natural Minor Scale in my DAW

Minor scale degrees offer a distinct, more introspective (almost depressing) sound compared to their major counterparts.

#1. In an A natural minor scale (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A), the first scale degree (A) acts as the tonic of course, providing the foundational note that sets the key’s mood.

Similar to how the tonic functions in major keys, just with a darker undertone.

#2. The second scale degree (B) serves as the supertonic, adding a gentle sense of tension that can lead smoothly to the subdominant or dominant.

For example, in progressions like ii°-v-i (B diminished – E minor – A minor), the supertonic creates a soft buildup that keeps the overall mood somber.

It’s used the most when it comes to more reflective sections of songs where some much-needed anticipation should be.

#3. The lowered third scale degree (C) is a defining feature, giving the minor scale its signature somber tone.

In genres like trap or indie music, starting a melody on the third scale degree hypes up the sad or moody feel, immediately differentiating it from its major counterpart.

You can also use the third degree in minor triads to deepen the emotional impact of your harmonies as well.

#4. The fourth scale degree (D) builds additional pre-dominant tension, used in longer, more dramatic chord progressions.

For example, in i-iv-VII-i (A minor – D minor – G – A minor), the subdominant (D minor) serves as a bridge that builds suspense before resolving back to the tonic.

This makes it great for creating longer phrases or sustained sections that gradually build tension.

#5. The fifth scale degree (E) retains its function as the dominant, providing resolution but with a softer pull compared to major scales.

In the minor ii°-v-i progression, the dominant chord (E minor) doesn’t have the same strong leading effect as it does in major.

So what you’ll get is a more open-ended feel that fits lo-fi and moody hip-hop production best in my opinion, so if that’s your genre, definitely play around with this.

#6. The sixth scale degree (F) in minor keys can soften the mood without changing the scale.

You’ll hear this a lot in slower, more atmospheric tracks where the submediant (F) is used to create emotional tension.

#7. Finally, the seventh scale degree (G) lacks the strong leading quality found in major scales, which is why minor melodies feel more open-ended, so to speak.

This allows for a smoother transition between phrases, which is perfect for ambient music, where lingering notes create a super dreamy vibe.

TIP: Try using the second and fourth scale degrees in minor melodies to enhance the tension and depth of the musical line.

This is especially useful for trap, lo-fi, or moody hip-hop tracks, where the darker undertones of the minor scale can add complexity and emotional impact.

Side note, we also got you if you want to learn all about the minor scale as well.

Breaking Down the 7 Scale Degrees (In Detail)

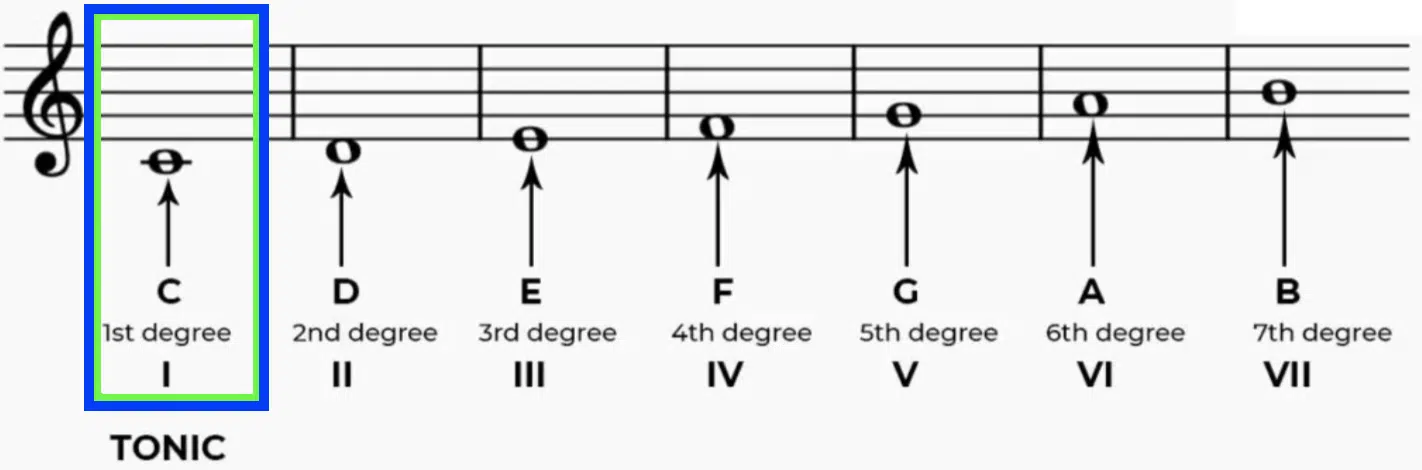

Now that we’ve explored the basics of major and minor scale degrees, let’s break down each of the 7 scale degrees in general. Each scale degree plays a unique role, bringing its own vibe, tension, or resolution to your music, so it’s super important to know. The following examples will be in both C Major and A minor.

-

First Scale Degree (Tonic): The Root of All Harmony

The first scale degree, known as the tonic, is the foundation of any scale 一 it’s the note we return to and the one that defines the key signature.

For example, in a C major scale, the tonic note is C, while in an A natural minor scale, it’s A.

The tonic note gives your music a sense of home or rest, and melodies often start or end on this note to provide a sense of resolution.

When creating chord progressions, you can use the tonic chord (e.g., C major in the C major scale) as a starting point to dictate the mood of the track.

PRO TIP: Try playing around with melodies that repeatedly land on the tonic and you’ll instantly see how it naturally feels stable and satisfying, setting the tone for your piece.

-

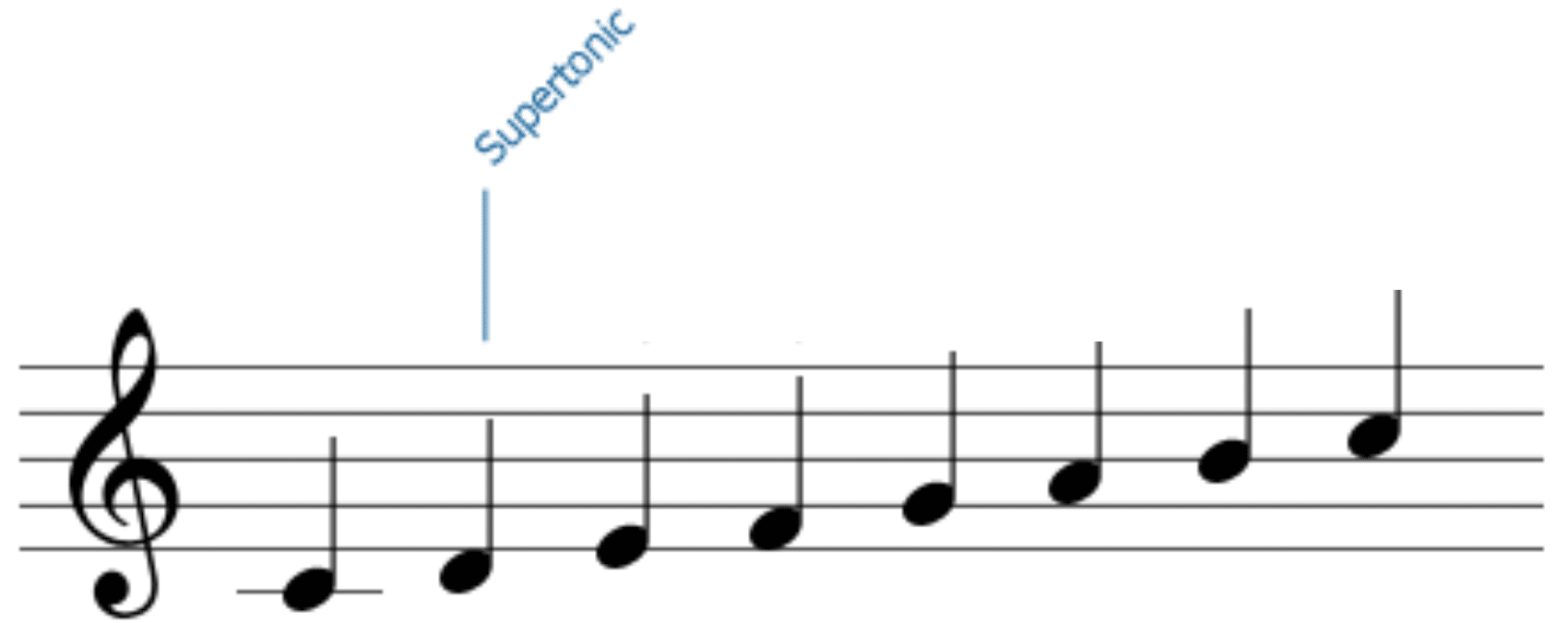

Second Scale Degree (Supertonic): Adding Tension & Color

The second scale degree (supertonic), plays an important role in adding tension and movement to melodies.

In a C major scale, the second scale degree is D, while in A minor, it’s B.

It’s very popular for simple progressions like ii-V-I, where it helps create momentum toward the dominant and tonic chords.

You’ll find that starting a melody on the supertonic can add a sense of anticipation which people love, as it’s just one step away from the tonic note.

For example, using the D minor chord (built on the supertonic in C major) can add color to your progression, especially when transitioning to the G major chord (the dominant).

PRO TIP: When you want to build energy in your melodies, try using short melodic phrases that resolve from the supertonic to the tonic.

It creates a smooth and natural shift.

-

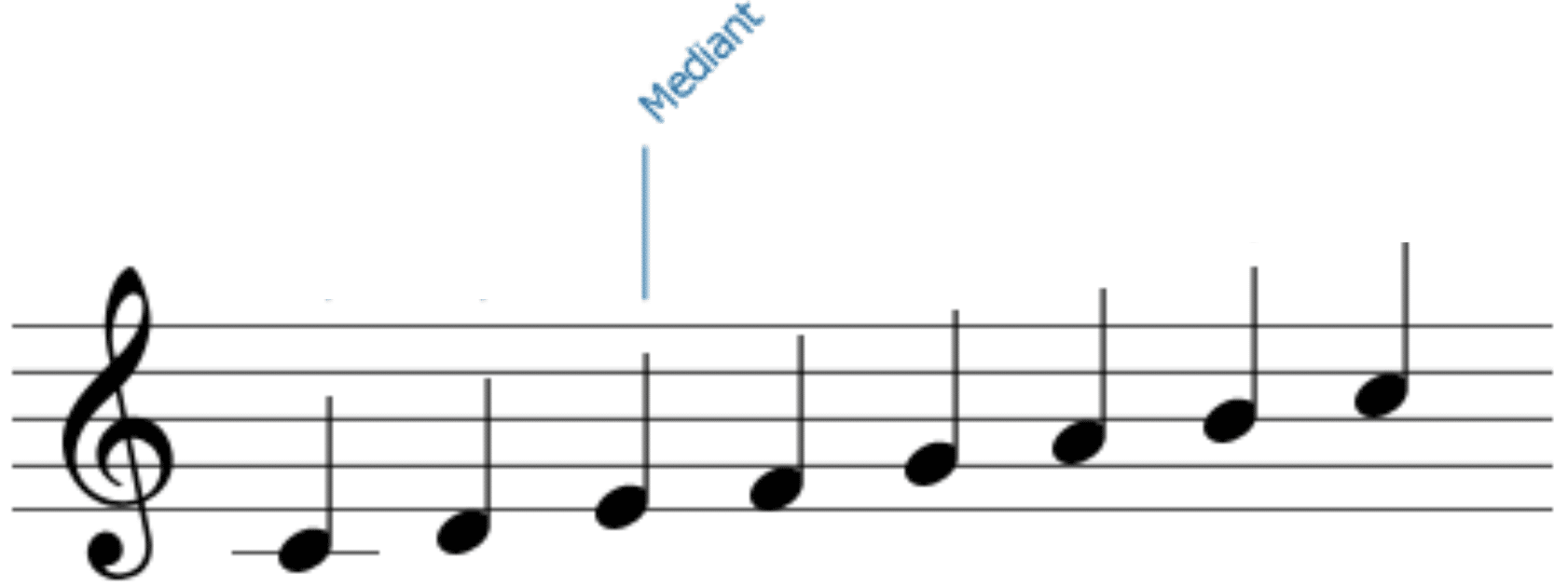

Third Scale Degree (Mediant): Establishing Major or Minor Tonality

The third scale degree, known as the mediant, is essentially your compass for telling whether the scale is major or minor.

- In a C major scale, the third scale degree is E which creates that bright, uplifting sound people are instantly drawn to.

- In a C minor scale, the third scale degree becomes E♭ which gives the scale its darker character (very sad yet intriguing).

The mediant is often used in melodies to establish the tonality of a track, especially in genres like pop or R&B, where the “feel” of a song shifts dramatically with just this note.

For example, emphasizing the E note in C major helps reinforce its major tonality, while focusing on E♭ in C minor enhances its somber vibe.

PRO TIP: Try adding the mediant as a melodic high point in your tracks to clearly establish whether you’re working with major or minor scale degrees.

-

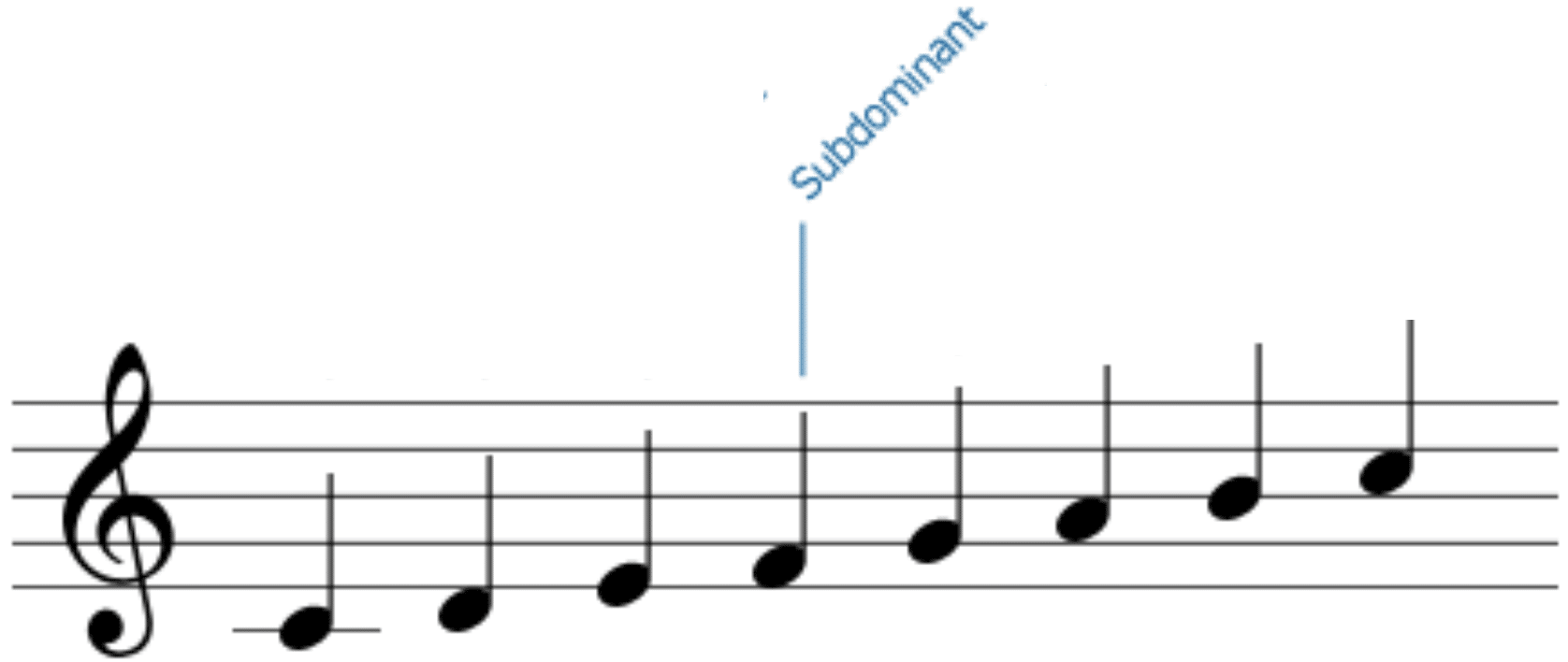

Fourth Scale Degree (Subdominant): Building Pre-Dominant Tension

The fourth scale degree (subdominant) creates pre-dominant tension and serves as a bridge between the tonic and dominant chords.

In C major, the subdominant is F, while in A minor, it’s D.

When used in chord progressions, the subdominant chord (like F major in C major) builds suspense and prepares listeners for the dominant or tonic resolution.

It’s a common technique in genres like pop, rock, and even classical music, where the IV chord is often used in the verses to create movement toward a more climactic chorus.

If you want to add emotional depth, try emphasizing the subdominant note in your melody lines… It will add a sense of “waiting” that keeps listeners hooked.

Just like in life, we always want what we can’t have, am I right?

PRO TIP: Use the fourth scale degree to extend phrases and delay the sense of resolution, which can make your chord progressions feel more dramatic/dynamic.

-

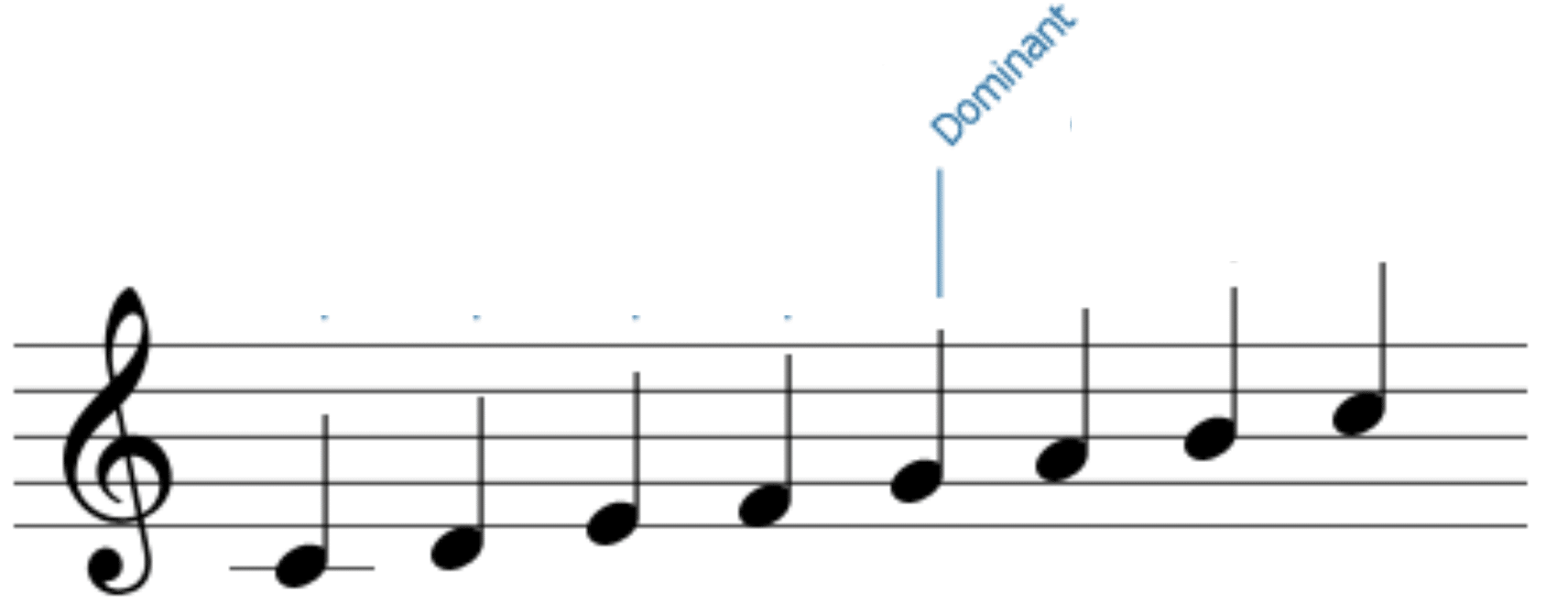

Fifth Scale Degree (Dominant): Creating Resolution & Drive

The fifth scale degree, also known as the dominant, is one of the most powerful elements in music theory.

In C major, the dominant note is G, while in A minor, it’s E.

The dominant chord (e.g., G major in C major scale) creates tension that demands a return to the tonic, making it essential in both major and minor progressions.

You’ll often hear the V-I (dominant-to-tonic) progression in nearly every genre in existence, literally, from pop and EDM to jazz and classical and everything in between.

If you want to make your melodies more impactful, use the fifth scale degree as a launching point because it drives energy towards the tonic.

Again, it’s all about reeling your listeners in and keeping them wanting more.

PRO TIP: Emphasize the fifth scale degree in choruses or climactic moments to create a strong, satisfying close to your musical phrases.

-

Sixth Scale Degree (Submediant): Exploring Subtle Changes in Mood

The sixth scale degree, also known as the submediant, brings a subtle shift in mood to add a layer of complexity to both melodies and harmonies.

In a C major scale, the sixth scale degree is A, while in A natural minor scale, it’s F.

It’s a powerful degree that’s used to transition between brighter and darker tones within a song (that much-needed push and pull).

For example, moving from the tonic to the submediant (like from C to A in C major) can create a more emo feel almost.

The submediant chord (A minor in C major), when used in progressions like I-vi-IV-V, adds a touch of nostalgia that’s common in genres like pop ballads or lo-fi tracks.

PRO TIP: Try incorporating the sixth scale degree into your melodies when you want to make a sudden shift from bright to totally chill.

While it’s certainly simple, it’s a super solid way to change the emotional direction of a track altogether, so don’t overlook it.

Oftentimes the littlest, most simple solutions can pack a huge punch when it comes to music theory.

-

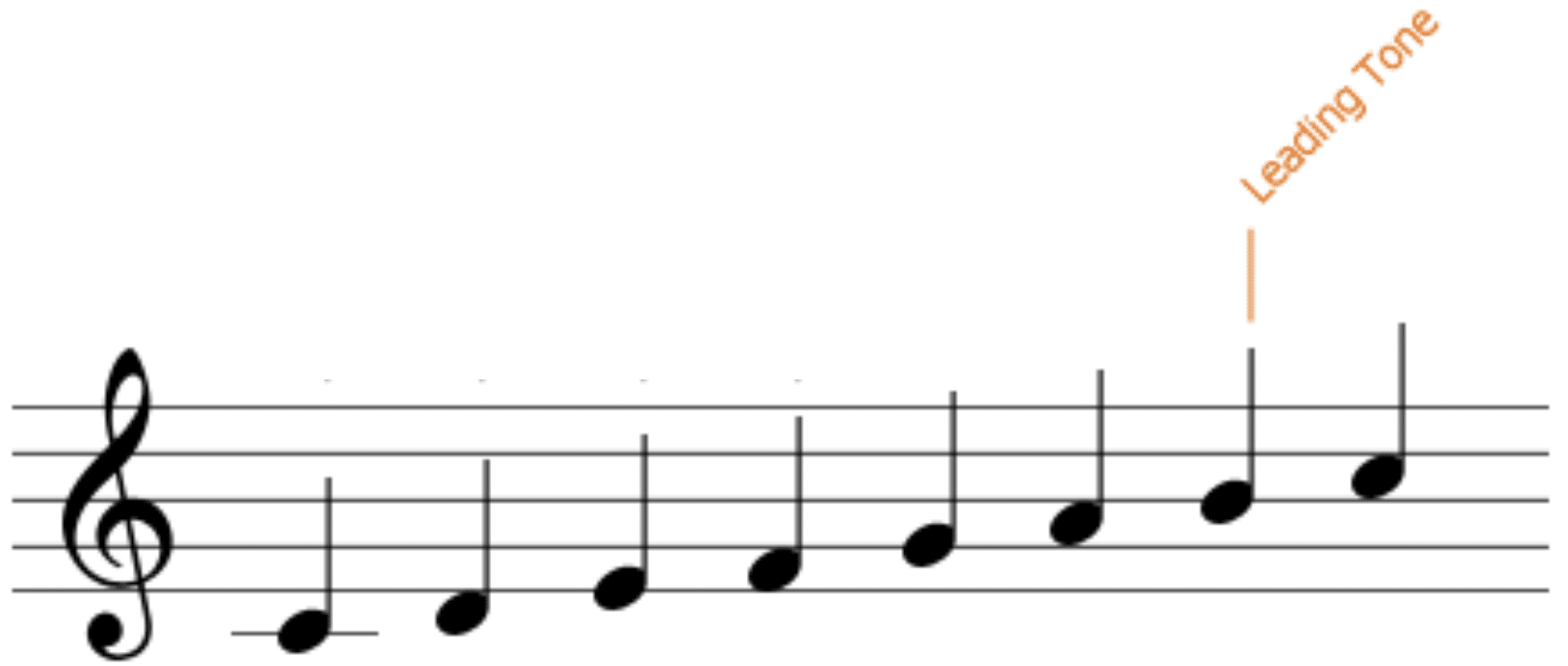

Seventh Scale Degree (Leading Tone): Leading Back to the Tonic

The seventh scale degree, often referred to as the leading tone, is super important for creating a sense of resolution 一 pulling listeners back to the tonic note.

In C major, the leading tone is B, and in A minor, it’s G#.

This degree adds anticipation and suspense, which makes it a popular choice for melodies that build toward a climax.

For example, if you’re laying down a melody in G major, you might use the leading tone (F#) as a tension point before resolving back to G, the tonic.

It’s especially useful in the V7-I (dominant seventh to tonic) chord progression, where the leading tone makes the final resolution feel even more satisfying than normal.

PRO TIP: Use the seventh scale degree to create climactic moments in your track.

It’s the perfect note to emphasize/let shine just before landing back on the tonic, making the return feel powerful and complete.

Advanced Scale Degree Tips, Tricks, & Techniques

Now that we’ve covered each of the seven scale degrees in detail, let’s explore some advanced techniques (my personal favs). These will help you use scale degrees more effectively in your melodies, chord progressions, and overall music production flow.

-

Relative Scales: How the Degrees Shift

Relative scales share the same key signature but have different starting points (start on different tonic notes), meaning the scale degrees shift accordingly.

You have both relative minor and relative major scales.

For example, the C major scale and A natural minor scale are relative because they both contain the same notes C, D, E, F, G, A, and B (no sharps or flats at all).

However, the tonic note in C major is C, while in A minor, it’s A, shifting the emphasis of the scale degrees.

This change alters the role of each degree, making the third scale degree (E) sound bright in C major, while feeling darker in A minor.

The submediant (A in C major) acts as a point of emotional color, but when A becomes the tonic in A minor, it grounds the scale, bringing it back home as we spoke about.

Let me build a little picture for you…

Let’s say you were starting a phrase in C major and then switching to A minor, you’ll notice that the mediant (E in C major) becomes the fifth scale degree in A minor.

This creates a shift from major tonality to a minor, unresolved feeling that completely changes the vibe/mood of your track.

It makes it more versatile as a whole.

NOTE: When transitioning between relative scales, focus on how the mediant and submediant interact. These scale degrees define the overall mood shift between major and minor tonality.

-

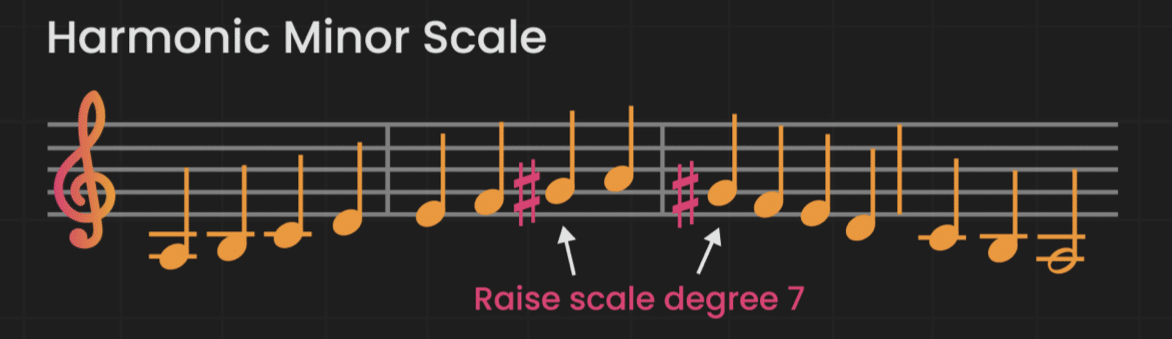

Scale Degrees in Harmonic vs. Melodic Minor Scales

The harmonic minor scale and melodic minor scale add unique twists to the typical natural minor scale because they change the roles of scale degrees.

In the A harmonic minor scale (A, B, C, D, E, F, G#, A), the seventh scale degree (G#) is raised by a half-step 一 creating a stronger pull back to the tonic note (A).

This alteration adds a dramatic feel, which makes it popular for cinematic scoring.

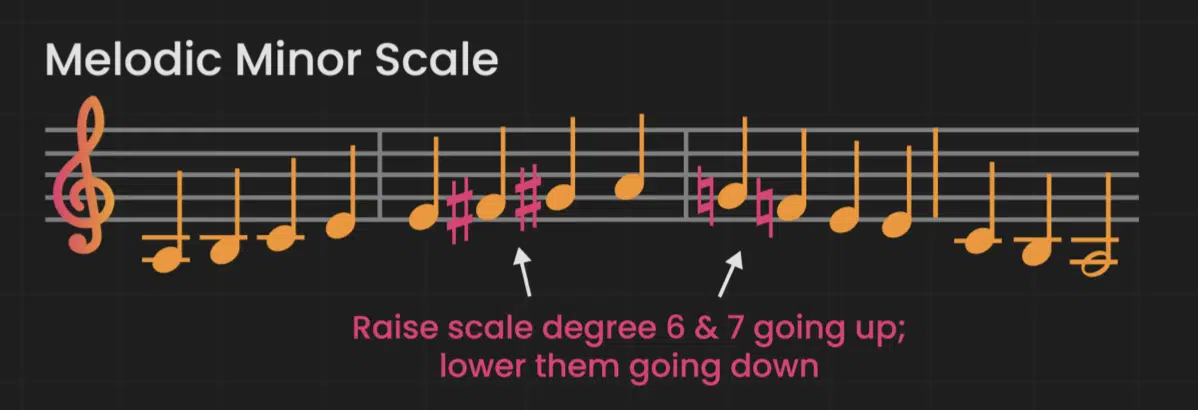

The melodic minor scale, on the other hand, raises both the sixth and seventh scale degrees when ascending.

For example, in the A melodic minor scale, you’ll play A, B, C, D, E, F#, G#, A when going up, which smooths out the melodic line.

It does this by reducing the gap between the fifth and seventh degrees.

When it’s descending, however, the melodic minor scale reverts to the natural minor scale, with F and G serving as the sixth and seventh degrees, respectively.

To make the most of these scales in your own tracks, try using the melodic minor scale in jazz improvisation, where its fluid motion enhances solos.

As well as the harmonic minor scale in dramatic buildups where the raised seventh degree creates tension before resolution.

It can really bring a unique, out-of-the box to any genre (and it’s all about starting new trends, am I right?).

-

Scale Degrees in Melodic Writing: Creating Catchy Melodies Like a Boss

Drill Melodies.

When laying down melodies, the choice of scale degrees can make all the difference in creating something memorable or lackluster.

Starting a melody on the fifth degree (like G in the C major scale) adds a sense of urgency, often driving the melody toward the tonic.

For example, try creating a phrase that starts with G, then quickly moves to the leading tone (B) before resolving to C…

The contrast between the fifth degree and the seventh degree will create tension and release and make sure the melody is more impactful.

In minor scales as opposed to major scales, emphasizing the third scale degree (like E♭ in C minor) can immediately set a more gloomy tone.

It’s perfect for genres like lo-fi, indie rock, or hybrid genres.

For instance, you could start a minor melody on E♭ and move to D (the second degree), creating a descending, mournful feel that fits darker, introspective tracks perfectly.

Adding the leading tone (seventh scale degree) near the end of a phrase builds anticipation, making the resolution back to the tonic note (C) feel more complete.

You can even try extending the leading tone with a longer note value or using vibrato to highlight the build-up before finally landing on the tonic.

For super catchy melodies, try combining the first, second, and fifth scale degrees in short, repetitive patterns which makes it easy/simple to remember.

Think about tracks where the hook gets stuck in your head 一 chances are, they lean heavily on these basic degrees.

It’s a tried-and-true method that works well in pop and hip-hop hooks all day.

Also, in trap or drill music, repeating a phrase built on the first and second scale degrees, with occasional jumps to the fifth, can create that signature bounce.

PRO TIP: Experiment with different combinations of scale degrees by humming simple phrases, paying attention to which notes create the strongest sense of movement and emotion.

-

Scale Degrees in Basslines: Driving the Groove, Baby

Scale degrees play a major role (pun intended) in shaping basslines, as the lower register emphasizes their overall harmonic impact.

In a C major scale, starting your bassline on the first or fifth degree (C or G) creates a strong foundation so it’s way more grounded.

Try switching back and forth between C and G in a simple rhythm pattern, like eighth notes or syncopated sixteenths, to create that driving feel we all know and love.

For even more groove, try alternating between the root (C) and the subdominant (F) in a pattern, as it adds both movement and weight/depth to your progression.

In minor scales, emphasizing the sixth scale degree (like F in A minor) can add a darker, more rhythmic feel, perfect for trap or hip-hop beats.

You can experiment by using F as a prominent note in a repetitive bassline pattern, creating a haunting, pulsing rhythm that complements the moody vibe of minor keys.

The leading tone is also useful in basslines, especially when you want to create a build-up that resolves to the tonic…

So, try using it in the final measure of a phrase for added suspense.

For example, in C major, try ending your phrase with B (the leading tone) before resolving back to C in the next bar, which is super popular in melodic trap joints.

PRO TIP: focus on the second scale degree in basslines when you want to add a bit of funkiness, as it’s just enough to create a bounce without straying too far from the tonic.

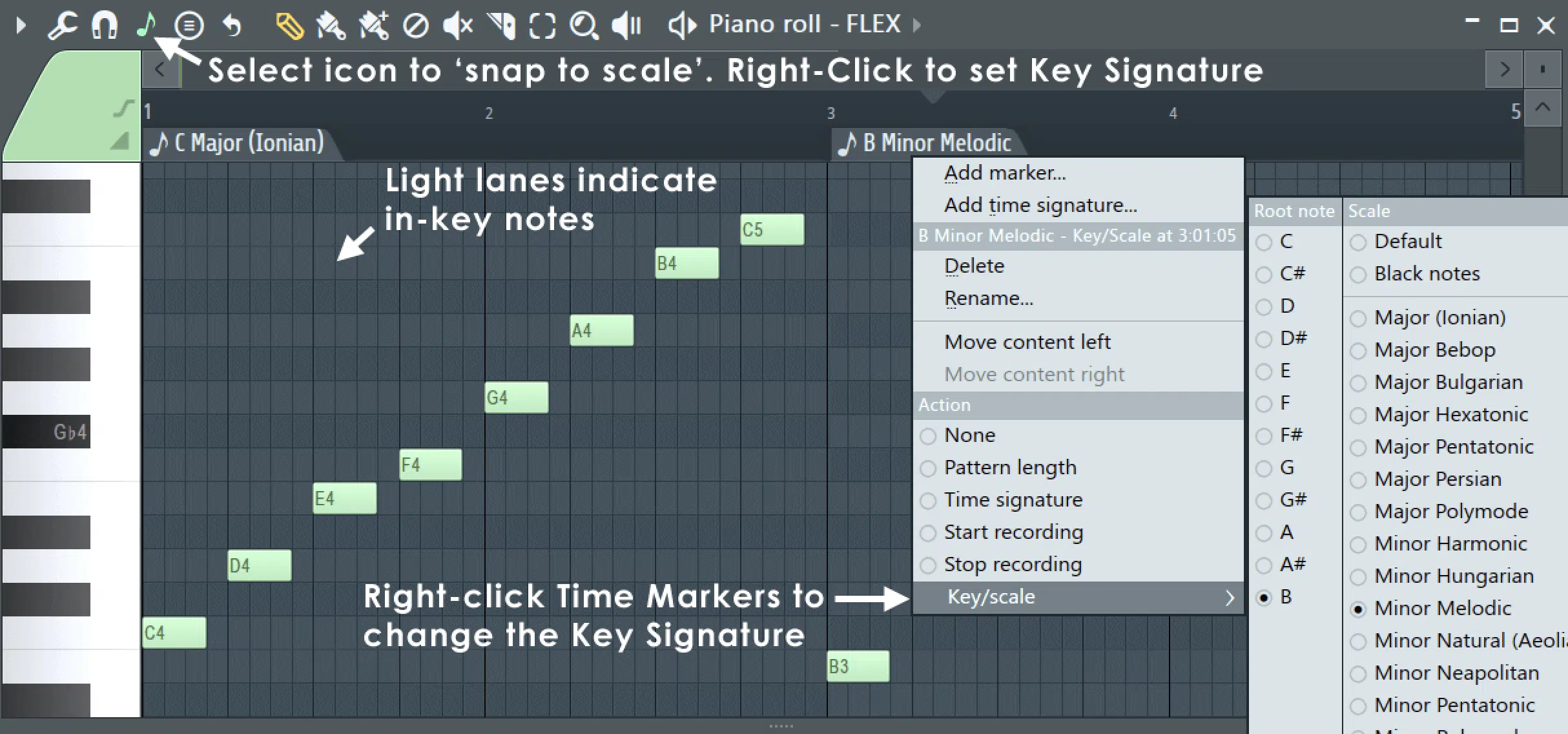

Pro Tip: And What are Key Signatures Exactly?

Key Signatures in FL Studio’s Piano Roll.

A key signature defines the specific sharps or flats that apply throughout a piece of music, setting the framework for both major and minor scales.

For example, the C major key signature is the simplest, with no sharps or flats, while G major has a key signature with one sharp (F#).

If you switch to the D major key signature, you’re working with two sharps: F# and C#, which makes the seventh scale degree (C#) lead back to the tonic(D) more strongly.

In contrast, A minor, the relative of C major, shares the same key signature 一 reinforcing that familiar minor tonality without any problems.

When playing in the F major key signature, you’ll encounter one flat (B♭), which directly alters the fourth scale degree and adds a warmer, softer feel to your melodies.

Understanding these key signatures helps you identify which notes are modified, impacting the overall sound of the scale degrees.

NOTE: If you’re trying to internalize key signatures to practice scales in all 12 keys, pay attention to how each change affects your melodic phrasing.

Whether you’re writing in minor scales like E minor, with one sharp in its key signature, or experimenting with melodic minor scales, knowing your key signatures is vital.

Oh, and always check the key signature before you start a piece, as it sets the tonal center and determines the roles of each scale degree from the first note.

Key Concepts and Variations in Scale Degrees

When working with scale degrees, there are several key concepts and variations to keep in mind, and I consider two of them to be most important.

#1. One of the most significant variations is the difference between the different minor scales, like:

- Natural minor scales 一 Follow the same key signature as their relative major scale but lower the third, sixth, and seventh scale degrees.

- Harmonic minor scales 一 Raise the seventh scale degree to create a stronger leading tone that pulls back to the tonic.

- Melodic minor scales 一 Raise both the sixth and seventh scale degrees when ascending. When descending, it returns to the natural minor scale to maintain that darker tonality.

Each one has unique scale degree numbers that alter the feel/function of a piece.

You might start with a natural minor melody, then shift to harmonic minor to heighten tension, or use melodic minor for a smoother, more flowing line in a solo.

The chromatic scale, for example, includes all twelve note names within an octave, which offers different ways to play around with any pitch class.

So you can go above and beyond standard major scales or minor scales and experiment with all scale degrees.

Side note, when you hear the phrase “enharmonically equivalent,” that simply means the same note can be represented differently depending on the key signature.

This could be something like G# and A♭.

#2. Another key concept is the role of whole steps and half-steps, which define the exact spacing between scale degrees.

Major Scale Whole-Steps & Half-Steps.

For example, in a major scale, the interval between the third and fourth degrees is a half-step (all about tension).

The natural minor scale, however, has a whole step between the second and third degrees, which softens the overall feel.

Understanding these concepts will help you knock out stronger melodies and harmonies (and understand music theory further).

These intervals shape the character of a scale.

Plus, influence the flow of melodies and harmonic progressions, which you should know as producers/songwriters.

This makes it way easier to shift between different key signatures while keeping the same scale degree names.

NOTE: You can always use the treble clef and bass clef to visualize scale degrees across octaves, helping you better understand how notes interact within a scale.

Final Thoughts

Scale degrees are a little more complex than you might have thought, am I right?

They not only shape your melodies and harmonies but also help define the overall mood and direction of your music.

By really nailing down how scale degrees work in different scales, you can create better melodies, stronger chord progressions, and more dynamic basslines like a pro.

To help you really understand chord progressions across popular genres, be sure to check out these insanely beneficial Free Sample Packs.

They’re packed with chord progressions from almost every genre you can think of, as well as killer melodies, basslines, and much more.

You’ll find not only basic scales and chords but also more advanced variations too.

And, there’s also a Free Project Files pack that shows you how to create a beat from start to finish 一 covering music theory basics and everything else you’ll need.

Remember, mastering scale degrees is a skill that can elevate your entire production process.

With consistent practice and experimentation, you’ll start to hear how each scale degree impacts the sound and feel of your tracks.

So keep pushing yourself, and you’ll soon be knocking out professional-level music with confidence and precision like never before.

Until next time…

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.